Tow truck work blends hands-on mechanical skill with regulatory compliance and customer-facing service. For Everyday Drivers, residents and commuters who depend on roadside assistance, Truck Owners managing fleets, Auto Repair Shops and Dealerships coordinating recoveries, and Property Managers overseeing on-site incidents, a clear path to qualification matters. This guide lays out the essential steps in five connected chapters: licensing and CDL endorsements, training and safety, background checks and employment prerequisites, gaining experience and career progression, and a realistic view of wages and regional demand. Each chapter builds on the previous one to provide a holistic view of what it takes to become a tow truck driver and how to navigate the job market with confidence.

Riding the Road to Readiness: Licensing, Endorsements, and Tow Truck Credentials

Entering the world of tow truck work starts long before the first call comes in. It begins with a clear map of licensing, endorsements, and the safety standards that keep the job from becoming a liability. The path is shaped by national guidelines and state specifics, but the core elements stay consistent: meet minimum age and license requirements, establish a clean driving record, pass testing, and complete specialized training that translates into practical on-the-ground skill. Tow trucks operate in a high-stakes environment where weight, leverage, and speed collide, so every credential is more than bureaucratic padding—it’s a tool for better, safer recoveries and reliable service for motorists in distress. If you’re plotting this career, the route depends on understanding how licensing and endorsements unlock the different classes of tow equipment and the kinds of jobs you’ll be qualified to take on.

First comes the baseline before any endorsement. In most U.S. states, you must be legally old enough to handle a commercial vehicle and to hold a valid driver’s license before pursuing a CDL. The exact minimum age can vary, with some jurisdictions allowing CDL applications as early as 18 and others requiring 21 for certain commercial operations. Beyond age, the noncommercial license remains a prerequisite because it demonstrates fundamental driving competence and familiarity with traffic laws before you graduate to heavier, more complex vehicles. A clean driving record matters as much as a clean driving test; a history of major violations or DUIs can disqualify you from towing roles or slow a budding career to a crawl. These are safeguards that help ensure you can handle the responsibility of guiding a heavy, less maneuverable vehicle through tense road situations while protecting others on the scene.

The heart of the licensing upgrade is the Commercial Driver’s License, the gateway to the tow truck profession. A CDL with a Tow Truck endorsement, often marked as a “T,” is typically required to drive a tow truck. Preparing for this involves passing a written knowledge test and a practical skills test. The practical portion is comprehensive and unforgiving in its expectations: you will be tested on a pre-trip inspection to demonstrate you know what you’re looking for and how to check for potential issues before you roll; a basic vehicle control portion to show you can manage a vehicle of weight and size with confidence; and an on-road driving test that places you in real traffic and real towing scenarios. Vision and hearing standards cut across both the knowledge and the performance tests, ensuring you can observe and respond under pressure. Some operators and state programs push you toward more advanced licenses, such as an A2 option, which opens the door to larger, heavier tow trucks used in demanding recovery operations. The details for A2 can be strict: older age requirements, years with a related license in certain configurations, and points accumulated must be monitored. A reference in the industry notes that pursuing this path commonly requires substantial prior experience with B1/B2 licenses and careful adherence to point limits, underscoring that higher-end towing gear carries higher responsibilities.

With the CDL and the T endorsement in hand, you’ll likely need specialized training specifically focused on towing operations. This is not optional padding but a necessary bridge between general truck operation and the delicate art of towing. Trainees learn how to safely secure vehicles, understand weight distribution, and operate winches, hydraulic lifts, and tow rigs in a controlled, predictable manner. They also study emergency response procedures and state-specific regulations that govern roadside recoveries. Some employers provide this training, while others require it as a mandatory step in the hiring process. In either case, the program you choose should be recognized by state authorities or industry associations, because certification of competency in towing practices translates into fewer costly mistakes on the road and a steadier workflow for you and your employer.

Beyond tests and training, the hiring process probes for reliability in the form of background checks and drug screenings. The logic is straightforward: a tow truck driver is often first on the scene of an accident or a vehicle breakdown, and the role demands discretion, trustworthiness, and the ability to follow safety protocols under pressure. A clean slate here matters as much as the mechanical skills you bring to the table. The combined weight of these checks signals to employers that you are someone who can be counted on when seconds count and when the job involves other people’s property and safety.

Gaining practical experience is a natural next phase after you earn the credentials. Many drivers begin as apprentices or assistant drivers, soaking up hands-on knowledge under the supervision of seasoned operators. This apprenticeship period is where theory meets reality: you learn how to read a scene, plan the sequence of securement steps, and adjust for different vehicle types and tow configurations. It’s also where you develop your professional demeanor—the calm, composed tone with dispatch, the careful approach to on-scene safety, and the readiness to communicate clearly with drivers, bystanders, and law enforcement. Experience is not just about racking up tows; it’s about building a track record of safe, efficient recoveries that comply with regulations and protect the vehicle being recovered, the drivers involved, and the road users around you.

As you advance, you’ll find that endorsements become more than checkboxes. The S endorsement, for example, is essential when you’re operating a vehicle with a towed unit that exceeds a significant weight threshold and that is likely to pull into highway recovery scenarios. The P endorsement may be necessary for towing operations that involve passengers onboard in certain specialized vehicles, and in some states you might encounter the N endorsement for tank vehicle operations in related contexts. The specific endorsements you need depend on the job profile you’re targeting and the state’s requirements, which is why it helps to keep a running conversation with a CDL instructor or a human resources professional who understands local regulations. The main thread remains intact: your ability to handle heavier gear safely multiplies the opportunities you’ll have to work on high-demand shifts, such as highway rescues or large-vehicle recoveries, which are often the most lucrative but also the most complex.

To keep this path coherent with the broader article on how to become a tow truck driver, consider the practical tip of consulting a state-by-state guide that breaks down the licensing steps, endorsements, and training options in one place. For readers who want to see the next steps mapped out clearly, the CDL Tow Truck Guide offers a concise, navigable overview of what to expect as you pursue these credentials. CDL Tow Truck Guide. This kind of resource is especially valuable when you’re coordinating a plan that aligns your ambitions with the realities of state laws, employer expectations, and the practical demands of tow work.

As you approach the end of the licensing phase, keep in mind that the journey continues beyond the classroom and the testing grounds. State rules, employer policies, and the evolution of safety standards all shape the ongoing education a tow truck driver needs. A commitment to continuous training is part of the job—whether it’s refreshing a pre-trip checklist, updating your understanding of weight distribution, or learning new safety protocols for on-scene management. In many ways, licensing and endorsements are not endpoints but gateways: they unlock access to the range of tow work that exists, and they anchor your credibility as a professional who can respond to emergencies with both expertise and restraint.

For official, up-to-date guidance on CDL requirements and endorsements, you can consult the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s resources. The FMCSA provides the authoritative framework that underpins state programs and employer requirements, helping you navigate the specifics without guesswork: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov

Tow Work Ready: Training, Safety, and the On-the-Job Skills That Power a Tow Truck Career

Tow work isn’t glamorous, but it’s essential. Becoming a tow truck driver means joining a field that blends mechanical skill, quick thinking, and a steady nerve. The path is defined by clear requirements, targeted training, and a disciplined approach to safety. This chapter traces that path in a single, continuous arc—from the first steps of eligibility to the daily habits that keep you reliable on the highway and the shoulder of the road. The goal is not just a license, but the competence to protect lives, assist stranded motorists, and maintain a fleet’s reputation for trustworthiness.

First comes eligibility, the gate that separates aspiration from practice. You must be at least 18 years old to pursue a commercial license in many states, though certain jurisdictions or employers might require 21. Holding a valid driver’s license is non-negotiable; you’ll need a clean record because insurers and employers insist on safety-first behavior. A background check and drug screening often accompany the hiring process, signaling the importance of reliability in a role that frequently places you in high-stress, time-sensitive situations. These prerequisites form the baseline for every veteran driver, because the job hinges on predictability and public safety.

Beyond meeting the age and license criteria, the core step is obtaining a Commercial Driver’s License with the right endorsement—usually a Tow Truck designation noted as a “T.” This isn’t a generic CDL; it’s a qualification that recognizes the added risk and responsibility of towing large vehicles. The path to a T endorsement typically begins with a written knowledge test, followed by a skills assessment. The skills test includes a pre-trip inspection, basic vehicle control, and an on-road driving segment. Vision and hearing checks are standard, ensuring you can observe hazards and communicate effectively with other road users. Some operators pursue a more advanced A2 license in jurisdictions that require operating larger, heavy-duty tow trucks. The A2 route has age and experience conditions, but it serves a specific niche where payload and maneuvering demand peak precision. The exact requirements vary by state, so it pays to check the department of motor vehicles in your area, but the overarching theme remains simple: you earn the privilege to tow by proving you can operate safely and responsibly under challenging conditions.

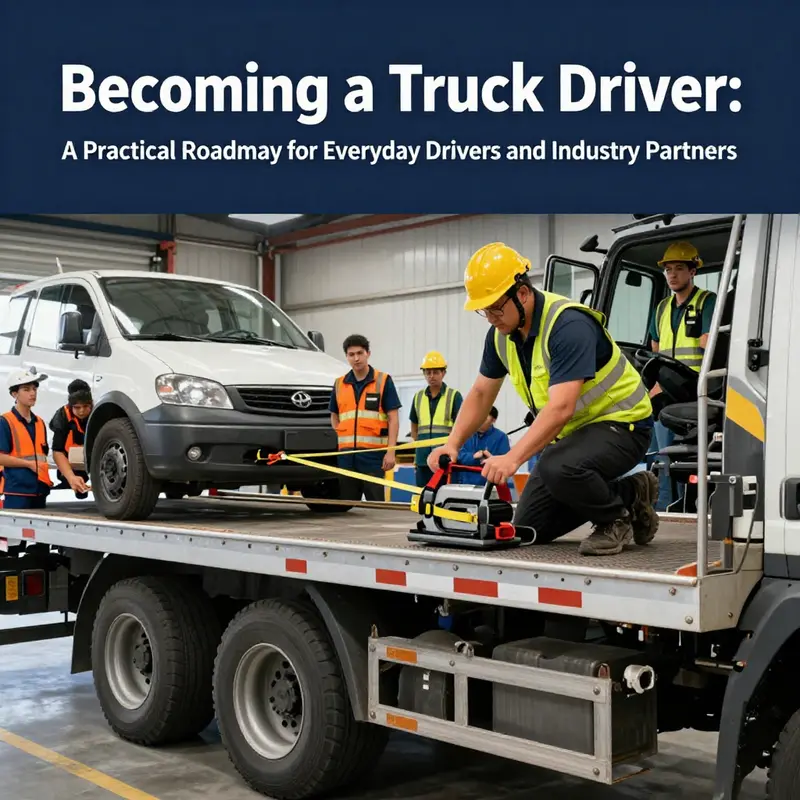

With licensing in hand, the real work begins—specialized training that translates theory into practice. Tow truck operation training covers the anatomy of the fleet: flatbeds, wheel-lifts,rollback units, and other recovery configurations. Each type requires different securing methods, different winching approaches, and different limits on weight and leverage. You’ll learn how to select the proper equipment for a given scene, how to apply chains, binders, and chokers correctly, and how to protect the vehicle under load from shifting damage. Essential hands-on skills include performing a meticulous pre-load inspection, establishing a safe recovery plan, and executing a controlled lift and tow while maintaining a stable center of gravity. Reputable programs—offered by vocational schools, community colleges, and professional associations—provide simulations that mimic roadside encounters. Some employers also supply company-specific training, which helps align your practice with real-world procedures and the equipment you’ll use every shift.

The training doesn’t stop with mechanics. Safety is the unmovable compass guiding every decision a tow operator makes. Personal protective equipment, or PPE, is more than a fashion statement. High-visibility apparel, gloves, and eye protection are standard when you’re operating on or near busy roadways. Scene management is taught so you can shield yourself, your team, and bystanders with cones, flares, and warning lights. You’ll study proper lifting techniques to prevent back injuries, leaning on mechanical aids when possible and following ergonomic guidelines as a discipline. Emergency response training is often included because roadside incidents can become volatile quickly. Some programs integrate first aid or CPR certification, a practical complement to technical know-how. The result is a driver who not only completes a tow but also stabilizes a scene, reduces risk, and preserves life and property.

On the job, those skills mature into a set of core competencies that separate good tow drivers from excellent ones. Communication becomes a daily tool for coordinating with police, motorists, insurance adjusters, and fleet managers. Clear, calm communication helps de-escalate tense moments and speeds up the resolution when a scene is chaotic. Problem-solving and quick decision-making are essential because every tow presents a unique intersection of vehicle condition, roadway geometry, and traffic patterns. You’ll need to assess damage, choose the right recovery method, and map a safe route that minimizes exposure to danger. Time management and flexibility go hand in hand with unpredictable hours—nights, weekends, holidays, and weather events all demand adaptability. And because your work intersects with customers during stressful moments, customer service becomes a professional habit. A courteous, professional demeanor fosters trust and can translate into repeat business for the company you represent.

Gaining practical experience is the bridge from theory to independence. Many new drivers start as apprentices or assistant drivers, learning the rhythms of dispatch, call volume, and the choreography of a tow truck operation. These early roles provide a protected space to build muscle memory for securing vehicles, using winches without compromising safety, and interpreting incident scenes. It’s common for an emerging driver to rotate through different tasks—on-call shifts, roadside assistance calls, and light-duty recoveries—so you can observe how different scenarios demand different tactics. As you accumulate hours, you’ll gain confidence in selecting equipment, judging weight distribution, and maintaining composure when the clock is ticking. Employers value reliability; showing up on time, following procedures, and documenting details accurately can become your strongest endorsements when opportunities to operate solo arise.

Finally, the pursuit of a tow truck career is inseparable from a commitment to continuous learning. The field evolves as equipment improves, regulations change, and best practices emerge from incident reviews and industry workshops. Stay engaged with ongoing training, participate in safety drills, and absorb lessons from every call, even the ones that tested your patience. You’ll also want to keep a pulse on the regulatory environment—some regions modify licensing requirements or introduce new safety standards, and those changes ripple through your daily work. When you’re ready to apply, target towing companies, roadside assistance providers, and municipal services with a narrative that emphasizes reliability, safety, and client service. It’s advantageous to demonstrate how you’ve translated training into measurable outcomes—lower incident rates, faster response times, and positive feedback from supervisors and customers.

For a practical, step-by-step orientation to CDL requirements, you can consult a concise guide specifically focused on tow-truck licensing. That resource aggregates the core elements of the licensing process—knowledge tests, skill tests, endorsements, and age considerations—into a pragmatic roadmap you can reference during your preparation. It’s a useful anchor as you map your path from curiosity to qualification. Additionally, the career path is seldom linear; you may begin in a support role or as an apprentice, then progressively assume more complex towing duties as confidence and credentials build. The arc of growth in tow work favors hands-on experience, disciplined practice, and a patient, safety-first mindset.

In this field, your reputation travels with every call. Your ability to secure a vehicle without causing additional damage, to manage a scene with confidence, and to treat customers with respect matters as much as your rolling skill. The job invites you to solve problems in real time, to adapt to changing conditions, and to support people at their most vulnerable moments. It rewards endurance, but it also offers clear milestones—licensing, training, supervised practice, and eventual independence. If you’re ready to pursue this path, start by confirming your eligibility, then enroll in a certified tow-operation program, practice diligently, and seek opportunities to gain real-world experience. The road to becoming a tow truck driver is a measured ascent, but it leads to a career that is essential, recognizable, and personally rewarding.

For practical orientation on licensing, you can reference a concise CDL-focused guide, which consolidates the licensing steps—knowledge tests, skill tests, endorsements, and age thresholds—into a clear preparation framework. You can also explore how the career path often begins with a supportive role or apprenticeship, then evolves as credentials accumulate and confidence grows. The journey values methodical practice and a safety-first mindset, not shortcuts. When the time comes to apply, you’ll have a story built on verified theory and tested practice: eligibility confirmed, training completed, and a track record of dependable performance under pressure.

To ground this chapter in official context, consider the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics as a comprehensive resource for duties, education requirements, salary trends, and employment outlook in heavy vehicle work. This external source anchors the discussion in verified data that underpins the practical steps described here. External resource: https://www.bls.gov/

Note: Internal resource for further program-specific guidance is available in the industry pages, including targeted CDL information. For a focused reference on the licensing pathway, consult the CDL tow truck guide linked here: CDL tow truck guide.

Tow Truck Driver Prerequisites: Gatekeeping, Licensing, and the Path to Certification

Tow truck work begins with a clearly defined set of prerequisites that ensure safety, reliability, and public trust. This chapter explains the gatekeeping: age limits, licensing steps, background checks, and screenings that determine who can enter the field. The journey starts with basic age and license readiness, then moves to a commercial credential tailored to towing. In many places you must hold a valid driver license before pursuing a commercial license, and you may encounter a minimum age that varies by state. A clean driving record is valued highly because tow operations occur in dynamic and high risk environments where errors can have serious consequences. Employers and insurers look for steady performance, responsible decision making, and a history of safe driving. After the general eligibility, the focus shifts to the CDL with a towing endorsement. The T endorsement confirms training in securing loads, operating tow related equipment, and handling the specific challenges of recovery work. The testing sequence typically includes a written knowledge test, a practical skills test, a pre trip inspection, vehicle control, and an on road driving assessment. Vision and hearing standards are part of the baseline requirements too. Some jurisdictions offer additional licensing paths for heavier models, such as an A2 option, which may carry its own age and history prerequisites. Alongside licensing, most employers require training that translates theory into hands on skills for securing vehicles, using winches and lifts, and managing weight distribution during towing. Training is often provided by the employer, and it can be mandatory to ensure everyone understands safety protocols and best practices. Screening and background checks are standard, sometimes including drug testing as part of the hiring process. A clean record and a demonstrable history of reliability support safe operations for the driver, the towed vehicle, and other road users. Progressive exposure through supervised work, apprentice roles, and gradual responsibility helps new drivers gain confidence and competence. When planning your path, map your local licensing ladder and the endorsements required for towing, then set a realistic timeline for training and testing. Maintain a plan to protect your record by driving responsibly and addressing incidents transparently. Finally, stay informed about policy updates, as licensing rules and safety standards do evolve. For practical guidance, you can consult a concise resource such as the CDL tow truck guide at https://winchestertowtruck.com/cdl-tow-truck-guide/

Tow Truck Trajectory: From Apprentice to Independent Operator

Tow truck driving is more than moving cars; it is a frontline blend of technical skill, people sense, and steady judgment under pressure. The path unfolds in stages, each building on the last: meet the basics, earn the credentials, practice with purpose, and gradually shoulder more responsibility. This chapter follows a practical arc for anyone who wants to turn a job on the roadside into a durable, scalable career. It is a journey of learning to move safely, serve calmly, and grow from assisting at scenes to guiding a small operation or leading a team. The road teaches that reliability matters more than bravado and that your reputation is built one careful call at a time. If you picture a tow truck as a moving link in a larger system—police, hospitals, insurers, repair shops—you begin to see why the steps you take early on matter so much later.

The first mile is the legal mile. In most places you must be at least 18 to apply for a commercial license, though a few states or countries raise the threshold to 21 for certain endorsements. You cannot even begin the CDL process without a valid non-commercial driver’s license in hand, which means your driver’s record starts to matter long before you ever hook a tow rope. A clean driving record isn’t merely about avoiding tickets; it signals to insurers and employers that you are predictable, responsible, and capable of making sound, safe decisions under stress. Expect background checks and drug screenings as part of the hiring process. These checks are not just bureaucratic hurdles; they are a gate to a role where you will encounter people in distress, operate heavy equipment, and work nights or during adverse weather. The discipline you show in the pre-employment phase often translates into how smoothly you will handle a roadside emergency the night your partner is counting on you.

With the basics in place, the core credential becomes essential: a CDL with the appropriate endorsement for towing. Tow operations commonly require a “T” endorsement, and many fleets look for Class B or Class A privileges when heavy or oversized loads are part of the job. The testing regimen is structured to verify both knowledge and practical skill. You will pass a written knowledge test that covers regulations, safe operation, and loading principles. Then you face a skills test consisting of a pre-trip inspection, basic vehicle control, and an on-road driving segment. Vision and hearing standards cap the process, ensuring you can perceive hazards and respond promptly. Some operators describe an A2 pathway for larger, heavy-duty equipment, a route that is selective and dependent on prior experience, but the pragmatic outcome remains straightforward: you must demonstrate capability, discipline, and a clear safety mindset before you touch a tow truck on live assignments. The endorsement process is not merely bureaucratic; it is your first formal acknowledgement that another level of responsibility now rests on your shoulders.

After earning the CDL, you typically enter a phase of specialized training tied directly to towing operations. This training covers how to safely secure vehicles of various sizes, how to operate winches and hydraulic lifts in confined spaces, and how to balance weight and load distribution to prevent tipping or gear failure. You learn to adapt rigging for different surfaces and vehicle configurations, and you practice scene management—how to stage your vehicle, set proper lighting, and direct bystanders without escalating risk. Crucially, you develop an understanding of how to respond to emergencies: how to stabilize a compromised vehicle, how to avoid secondary incidents, and how to communicate clearly with dispatchers and first responders. Employers often provide this training, but it is typically mandatory, and the deeper your mastery, the more options you will have when career growth presents itself. The technical side goes hand in hand with a growing intuition about when to act quickly and when to pause to reassess.

The hiring process also puts a premium on reliability and character. Reputable employers want drivers who can stay calm on a windy, wet, or icy night, who can maintain composure when a frustrated customer needs reassurance, and who can follow procedures even when the clock is ticking. A clean record is not simply about past mistakes; it signals your capacity for careful, deliberate action and your respect for the rules that protect you and others on the road. Drug screening, background verification, and ongoing monitoring of driving behavior are standard components of most driver programs. When you combine CDL credentials with a solid safety record and a reputation for punctuality and courtesy, you position yourself for better dispatch assignments, more predictable hours, and a reliability rating that attracts repeat clients and steady shop partnerships. The work grows more rewarding as you see your own consistency translate into fewer hazards and quicker, smoother recoveries.

Experience, however it is gained, becomes your real differentiator. Many drivers start as apprentices or assistant drivers, learning under the supervision of seasoned professionals who know the local terrain, the common roadside hazards, and the quirks of the region’s road networks. The early days are a hands-on immersion: you learn how to secure vehicles of all sizes without causing damage, how to operate winches with precision, how to menage the tarp, chains, and straps without tangling or slipping, and how to communicate with distressed motorists in a way that is calm and reassuring. You will also build a practical toolkit beyond the truck: strong communication with dispatch, solid time management to coordinate multiple calls, and an understanding of vehicle downtime that helps you guide customers through the process with transparency. Step by step, you assemble a professional temperament that blends technical finesse with customer service. As confidence grows, you may assume independent towing duties, handling calls with less direct supervision while continuing to refine your techniques and your safety routines.

As you accumulate experience, specialization becomes a natural next step. Some drivers gravitate toward accident response, where the stakes—fatigue, high-stress scenes, and complex recoveries—require a steady, disciplined approach. Others concentrate on heavy-duty hauling, where weight, distance, and environmental conditions demand advanced rigging and meticulous planning. With specialization come new demands: larger equipment, more elaborate planning, and closer coordination with law enforcement, emergency services, and insurance adjusters. Leadership roles also emerge, whether in dispatch or fleet supervision, where you guide a team, coordinate response to incidents, and optimize operations for efficiency and safety. An established reputation and a proven safety record can even open doors to entrepreneurship, allowing you to start your own tow business after building a solid client base and a network of service partners.

A clear, long-term plan helps translate these opportunities into a sustainable career. Set incremental goals: obtain the right CDL endorsements, complete mandatory specialized training, accumulate diverse towing experience, and stay current with changing regulations. Build a professional presence through a simple, organized collection of recoveries, safety checklists, and customer testimonials that demonstrate your reliability and diligence. This kind of documentation makes you a stronger candidate for supervisory roles or for independent ownership, and it also serves as a guiding compass when you evaluate offers from fleets, contractors, or municipal work. The path from apprentice to independent operator is a marathon, not a sprint, but it is a trajectory that rewards persistence, continual improvement, and a commitment to safety that protects you, your team, and the people you serve.

Finally, stay tied to standards and regulations as they evolve. CDL rules, hours-of-service limitations, weight classifications, and safety protocols shift over time, and the landscape of roadside assistance changes with technology and training methods. A driver who learns, mentors, and seeks feedback will adapt quickly and remain valuable in a demanding, essential trade. For a structured overview of CDL requirements for tow work, check the CDL tow-truck guide. This link anchors your early steps in a broader, well-documented framework that informs your decisions as you pursue specialization and leadership opportunities. And as you edge toward ownership or management, you can align with a broader ecosystem that includes repair shops, insurers, and municipal partners, ensuring your growth is supported by connections and continued learning. For broader industry standards and licensing guidance, consult authoritative sources such as the FMCSA: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov.

How to become a tow truck driver: Economic outlook, wages, and regional considerations

Tow truck driving sits at a practical seam where reliability, timing, and local demand meet the realities of road traffic and roadside emergencies. It is a job that rewards precision and dependability, but it also rewards geographic savvy. The economic landscape for tow truck drivers is shaped by how often roads clog, how often incidents occur, and how the industry deploys technology to connect drivers with help seekers. In 2025, the national average hourly wage stood at about $15.51, translating to roughly $32,260 per year for full-time workers on a standard 40-hour schedule. Those numbers, however, are a baseline rather than a ceiling. They illuminate the skill floor and the standard path, not the full spectrum of earnings that a capable, adaptable driver can achieve. Earnings diverge widely based on experience, the type of employer, and, crucially, where the work happens.

Regional variation is the most obvious determinant of pay. In dense metropolitan centers like New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston, the demand for rapid, reliable service is incessant. Here, base wages frequently outpace the national average, especially in high-traffic zones or during peak seasons—think winter weather events when accidents and impassable roads spike, or holiday travel periods when breakdowns spike along busy corridors. In California and New York, hourly rates can exceed the typical base by several dollars, reflecting both higher living costs and intensified service demand. Conversely, in rural or low-density regions, base pay may lag behind urban markets. Yet those drivers are often compensated with mileage bonuses, shift differentials, or the allure of quieter schedules that offer predictable hours. In practice, a driver who gravitates toward high-demand regions, or who is willing to work a flexible mix of day and night shifts, can see meaningful boosts to earnings even within a single state.

Beyond raw pay, the structure of the work itself influences earnings potential. The industry has begun embracing digital platforms that connect independent drivers with customers directly. Apps that present real-time job requests, integrated navigation, and income-tracking tools enable drivers to optimize their schedules, avoid downtime, and selectively accept jobs that fit their needs and constraints. This flexibility can be liberating for skilled drivers who want to balance earnings with reliability and safety. The ability to go online when available and go offline when needed supports a growing trend toward independent contracting, which often broadens the upper earnings envelope for experienced, trustworthy drivers who cultivate a steady reputation. At the same time, working through a traditional employer can provide stability, benefits, and a predictable workflow that some drivers prize. The best approach depends on personal priorities: steadiness and benefits or agility and control over one’s hours.

The relationship between pay and safety is real and measurable. A 2024 study by WT Ryley found that carriers located in counties where driver earnings are relatively high tend to experience fewer crashes. The implication is logical: better compensation can reduce fatigue, support longer tenures, and enable drivers to invest in ongoing training and safer operating practices. When drivers feel valued, they are more likely to stay on the job, maintain their vehicles, and follow best practices in securing loads and performing pre-trip inspections. This synergy between compensation and safety creates a virtuous cycle that benefits both drivers and the wider road network. It also underscores why regional strategies matter. If a carrier aims to improve safety outcomes, offering competitive wages in high-demand markets can be a practical, data-driven component of that effort.

Understanding the wage landscape requires seeing the whole career arc, not just the first paycheck. Entry into the field typically begins with obtaining a valid driver’s license, upgrading to a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL), and earning a Tow Truck (T) endorsement after passing the required knowledge and skills tests. The training at this stage lays the groundwork for safer, more efficient operations, including proper vehicle securing techniques, winching, weight distribution, and emergency procedures. Those foundational skills become more valuable as the driver climbs into more demanding assignments or moves into regions with greater density of service calls. Employers commonly provide or require specialized training after the CDL, ensuring that technicians understand how to handle a variety of tow scenarios—from light-duty to heavier recovery operations. The investment in training becomes a lever for higher earnings, especially when paired with a track record of reliability and a clean driving history, both of which are emphasized during the hiring process.

Another dimension shaping earnings is the strategic use of licensing and specialization. While the basic CDL with a Tow Truck endorsement unlocks the core capability, some regions and employers recognize additional credentials or classifications that permit operation of larger, heavier, or more specialized tow equipment. For instance, certain license pathways enable access to heavier-duty operations, which, in turn, broaden the range of assignments and the corresponding pay scale. In practice, drivers who deliberately pursue advanced licenses and maintain a spotless driving record create a strong value proposition for employers in both private and public sectors. Such credentialing often translates into steadier work in busy corridors, at airports, or along major highways where the volume of calls is high and the complexity of the job is greater.

A practical way to think about maximizing earnings is to balance regional choice, licensing, and platform strategy. Locations with higher demand—and thus higher pay—also tend to feature more opportunities to accrue a broader set of skills, from heavy-duty towing to accident response and vehicle recovery in challenging weather. In turn, the more you diversify your capabilities, the more you can cover in a shift. Some drivers prioritize peak-demand times, such as late-night hours or weekends, when service calls surge and comp time or higher hourly rates may apply—depending on local practices and employer policies. Others focus on building a reputation within a trusted platform, gradually increasing acceptance rates and improving response times. The result is a compounding effect: better responses lead to more calls, more calls lead to more reliable income, and a robust professional reputation helps sustain earnings during slower periods. For readers who want a quick reference, consider exploring our guide on Tow truck driver earnings. It provides a practical snapshot of how different arrangements—from employer-provided schedules to independent platform work—translate into real-world compensation.

Geography also intersects with cost of living, which in turn shapes the real value of wages. A wage that seems high in one city might feel modest in another once you account for housing, commuting, and local taxes. The savvy newcomer weighs not just the hourly rate but the total compensation package, which can include health benefits, retirement contributions, vehicle stipends, and reimbursement policies for fuel or maintenance. The more you align your career plan with local cost structures and traffic patterns, the more you can optimize both quality of life and take-home pay. As you consider these choices, gathering concrete data on regional demand and pay scales becomes essential. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics offers a comprehensive framework for understanding regional variations in tow-truck employment and wages, which can help you calibrate your expectations and plan a longer-term career path in the field. For official wage data, see the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics report.

From a strategic standpoint, the road to higher earnings is not just about chasing the highest-paying region. It’s about building a credible, multi-faceted profile: a clean driving record, a CDL with appropriate endorsements, hands-on experience from apprenticeships or entry roles, and a willingness to adapt to technological tools that improve efficiency and safety. The early training phase matters just as much as later career moves. Completing specialized training, mastering load securement, and learning how to handle emergencies with calm and competence yields dividends in the form of elevated job performance, more opportunities, and, ultimately, greater earning potential. In practice, this means actively seeking out continuing education, practicing incident-scene safety protocols, and maintaining the vehicle and equipment in peak working condition. It also means being selective about the shifts you take, balancing predictable income with the flexibility that platforms can offer.

Overall, the financial reality of becoming a tow truck driver is nuanced. It blends a foundational wage around a national average with a mosaic of regional pay scales, seasonal demand, and the growing influence of digital platforms that expand opportunities for independent work. Those who align licensing milestones, training investments, and geographic strategy—while sustaining a focus on safety and reliability—can navigate toward above-average earnings and a resilient, long-term career. The path begins with meeting the basic qualifications and progresses through disciplined skill-building, smart market positioning, and the prudent use of emerging tools to optimize schedules and outcomes. For readers charting this course, the payoff is not merely a paycheck but a professional role that keeps countless lives moving smoothly and safely on the road.

External resource for additional context: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes537011.htm

Final thoughts

Becoming a tow truck driver requires a clear sequence of steps: secure a valid CDL with the Tow Truck endorsement, complete specialized training, meet background and drug-testing requirements, accumulate hands-on experience, and understand the wage and regional landscape. By following this integrated roadmap, Everyday Drivers, residents, fleet owners, auto shops, and property managers can align expectations with real-world requirements, ensuring safer practices, reliable service, and dependable career growth in the towing industry.