Understanding the towing capacity of tow trucks is essential for everyday drivers, truck owners, and property managers alike. Whether you’re a commuter needing a reliable towing service, a truck owner curious about towing capabilities, or a property manager responsible for vehicle recovery, knowing how many vehicles a tow truck can tow plays a crucial role in your decision-making. Various factors come into play, including the type of tow truck, the size and weight of the vehicles involved, and road conditions. Through this exploration, we will examine the different types of tow trucks, the regulations governing towing capacities, and how vehicle types influence towing capabilities, equipping you with important knowledge for when towing services are required.

Tow Limits and Real-World Capacity: How Many Vehicles a Tow Truck Can Safely Tow

Tow trucks exist to solve a concrete, practical problem: moving damaged, stalled, or stranded vehicles without creating new hazards. The central question—how many vehicles can a tow truck tow at once—does not have a single universal answer. Instead, it hinges on a blend of equipment design, weight, vehicle dimensions, and the realities of the road. The answer favors safety and precision over math simplicity. A tow truck is not a conveyor belt; it is a carefully engineered machine whose capacity is defined by weight limits, balance, and stability as much as by the number of hooks and chains it can string together. When we unpack the factors behind capacity, a clearer picture emerges, one that helps responders, fleet managers, and motorists understand why a tow operation looks the way it does in the real world.

The first factor is the type of tow truck. Flatbed models, whether standard or rollback variants, carry a platform that carries the weight of the towed vehicle on the bed itself. The key distinction with flatbeds is not how many vehicles can be loaded in a line, but how much weight the bed and the chassis can bear from front to back. A damaged car is rolled or driven onto the bed and secured, and once the vehicle is immobilized or stabilized, the truck’s powertrain pulls the entire weight into motion. In many cases, the effective capacity is measured by weight limits rather than an arithmetic tally of vehicles. The same weight limit applies whether a single heavy car or several lighter vehicles are involved; the sum of weights must stay within the rated capacity.

Rollback tow trucks are similar in principle to flatbeds, but the platform slides back to the ground, allowing the towed vehicle to be pulled underneath and lifted. The critical factor remains weight: the bed must support the combined load, with the curb weight of each vehicle plus any additional equipment or securing gear. Because the bed’s length and construction constrain how much weight it can safely bear, the number of vehicles is less a function of stacking than of distributing a safe, balanced load across the platform.

Wrecker or crane-style tow trucks introduce a different dynamic. They use a rotating boom and winch to lift vehicles from difficult locations, often in recovery scenarios where wheels might not be aligned for drive-on towing. Here, the capacity is frequently expressed in tonnage, reflecting the maximum safe load the crane and chassis can manage at any given angle and radius. With a crane, the practical limit is not typically a line of vehicles but the safety of lifting and stabilizing a single, heavy salvage operation, followed by careful transfer and transport.

The second major factor is towing capacity, usually described in tons. This weight-based metric is the cornerstone of safe operation. A 20-ton tow truck, for example, has a theoretical ceiling of 40,000 pounds to haul in a single pull. But that limit is not a blank check to tow multiple vehicles totaling more than 40,000 pounds. It means the entire, cumulative weight at the hitch must stay within 40,000 pounds. As a result, you could tow one very heavy vehicle, or you could tow several smaller vehicles whose combined weight does not exceed that maximum. The details matter: if you tried to chain together a handful of heavier vehicles, you would quickly exceed the capacity and risk tipping, sway, or brake system failure. Conversely, a number of lighter cars can be combined to fill the weight target—up to the capacity limit—without compromising safety.

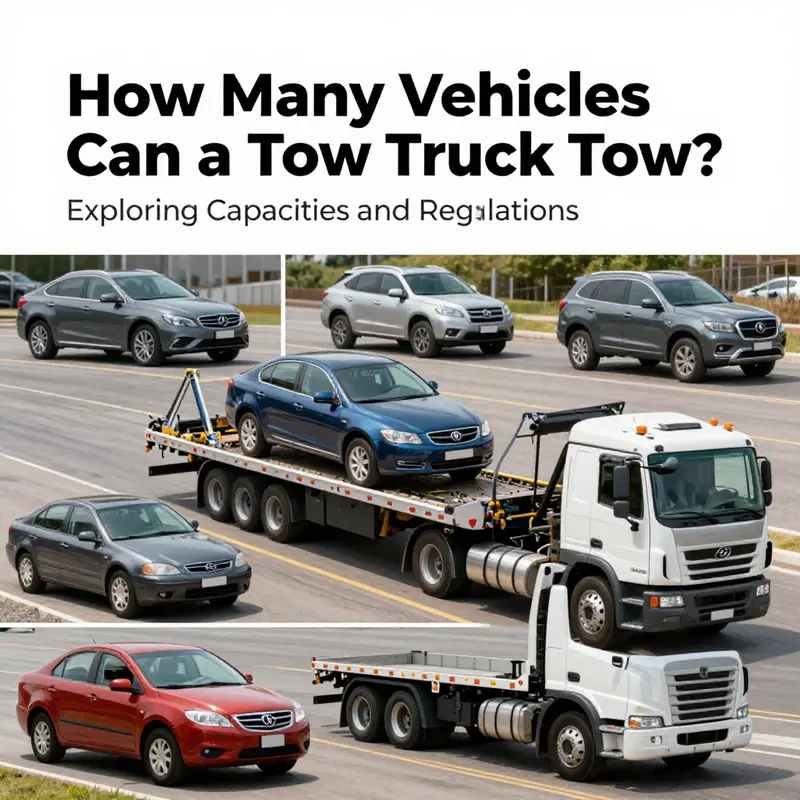

In practice, this weight-centered view translates into typical, general guidelines. Small tow trucks—those used for light-duty tasks or recovered from a local tow yard—tounders stand to tow only one vehicle, particularly if it is a compact or subcompact car. In many urban settings, a single craft vehicle is precisely what keeps traffic moving and scenes safe. Medium-sized tow trucks, such as those used for fleet recovery or dealership transport, can often move two to three standard-sized passenger cars, provided the combined weight does not exceed the truck’s rated capacity. Large and heavy-duty tow trucks, designed to recover or relocate multiple cars from disaster scenes or accident sites, hold the potential to tow four to six vehicles when the payload consists primarily of lighter sedans or compact vehicles. Yet even these figures are contingent on the weight distribution and the absence of large SUVs or light-duty trucks in the lineup. If the vehicles being towed are heavy SUVs, pickup trucks, or commercial vehicles, the capacity can shrink dramatically—sometimes down to a single vehicle—because maximizing stability and braking performance is paramount.

Additionally, the environment and road conditions cannot be ignored. A hill or grade places extra demand on the tow truck’s braking and traction systems. Wind, rain, icy surfaces, or uneven pavement complicate load control and acceleration. The combination of high wind, steep grades, and heavy weights can force operators to reduce the number of towed vehicles to preserve steering control and braking response. Road surfaces that are slick or uneven can lead to swaying loads or shifting weight, jeopardizing the alignment of the towed vehicles and the operator’s ability to keep the vehicle within safe lanes. The regulations governing these operations exist not as bureaucratic hurdles but as practical guardrails designed to prevent runaway loads, tire blowouts, or jackknifing.

Another important consideration is how the vehicles are secured and distributed on the tow platform. Even when a given weight limit allows several cars to be carried, poor balance or inadequate tie-downs can create instability. A misaligned load on a flatbed can cause the bed to tilt, or the towed cars to shift during transit, which increases the risk of damage to the vehicles and to the tow truck’s own structure. Consequently, professional operators calibrate their approach to each job: they assess the weight of the vehicles involved, evaluate the load distribution, and determine whether the operation calls for a single heavy tow, a pair of lighter tows, or a more complex, staged recovery. The aim is always to preserve the integrity of the towed vehicles, protect other road users, and stay within legal limits.

Legal and safety constraints frame the practical possibilities as clearly as the physical limits do. State and local regulations typically codify maximum permissible loads and require that operators demonstrate control and braking at the rated capacity. Exceeding the load limit is not just unsafe; it is illegal in many jurisdictions. Those rules compel a disciplined approach to tow operations: when in doubt, reduce the number of towed vehicles, or choose a larger, more capable unit if the mission demands it. The result is a system that prioritizes stability and safety over sheer throughput.

For readers drawn to the practical math behind these rules, it helps to keep in mind that capacity is a total weight matter, not a count of vehicles. A very large, high-weight vehicle can consume a sizeable fraction of the truck’s payload, leaving little room for additional towed cars. Conversely, a fleet of lighter cars might collectively stay within weight limits while still challenging the operator with maneuvering and securement tasks for multiple units. The overarching principle remains consistent: capacity is defined by safe hauling, balance, and the ability to stop and steer, not simply by how many vehicles are attached end-to-end.

To connect this concept to a handy, real-world resource, consider the idea that capacity is not just about the truck’s power but about its planning. When a dispatcher or operator evaluates a scene, they weigh the types of vehicles, their suspected weights, and the road to be traveled. If the objective is to move several standard cars from a stalled highway lane, a sufficiently strong medium or large tow truck may be appropriate, with the understanding that each vehicle adds to the load. When the scenario involves heavy-duty or specialty recoveries, it is common to use a specialized unit or staged operations. In short, the permissible number of vehicles on a tow truck is a function of total weight, weight distribution, and the operational environment—factors that together determine whether one, two, or more vehicles can ride safely on the platform. This approach ensures that the operation remains within the bounds of safety and law, while still achieving the objective of moving the vehicles efficiently. how much can my truck tow

From a broader perspective, this topic sits at the intersection of engineering design, traffic safety, and practical field experience. Tow trucks are not generic machines; they are purpose-built devices whose configurations reflect the kinds of missions they are expected to perform. The bed length, the strength of the winches, the strength of the securing points, and the lift capacity of any cranes all contribute to the ultimate decision about how many vehicles can be towed in a given situation. Operators routinely weigh the intended destination, the road profile, the vehicle weights, and the need for controlled deceleration and steering. Additionally, the recovery plan may call for staged loads, where a portion of the cargo is moved first, followed by the remainder after the initial safe transport is completed. This staged approach provides a practical path around the temptation to push a single truck beyond its comfortable limit.

In closing, while it is natural to ask for a simple number—how many trucks can a tow truck tow—the realistic answer is nuanced. The capacity is a function of a handful of interrelated factors: the type of tow truck, its weight rating, the weights and dimensions of the vehicles involved, and the conditions of the road and weather. When these elements align toward safety, a unit can perform more complex transports; when they do not, the operation becomes a careful, staged effort that respects the limits of the equipment and the road. The most important takeaway is this: capacity is about safe hauling, not about maximizing the number of vehicles attached. For those seeking a quick, practical snapshot, the best guidance remains a clear assessment of total load and balance, followed by a considered decision about whether one, two, or more towed units will be moved in a single, controlled operation. For further context on the broader technical landscape of tow trucks, see Britannica’s overview of tow-truck technology and safety.

null

null

Tow Truck Capacity Unleashed: Legal Limits, Safety Standards, and Real-World Calculations

The question of how many vehicles a tow truck can tow is rarely answered by horsepower or engine torque alone. In roadside operations, capacity is defined by physics, equipment design, and the regulatory framework that governs heavy recovery work. A practical view is that capacity is a safety-driven boundary rather than a fixed number, determined by weight limits, the configuration of the tow rig, and the road conditions at the moment of recovery.

In the United States, the baseline is set by the combination of the tow vehicle and the weight it is permitted to carry on interstate transport. Federal guidance through agencies such as the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration anchors a practical limit around a single towed vehicle in typical roadside recovery scenarios. The overarching rule in many jurisdictions is that a tractor unit towing a trailer may not exceed statutory weight thresholds, commonly framed around an 80,000-pound gross vehicle weight cap, which translates to roughly 36,287 kilograms. This figure is the practical boundary that informs every shift decision, from equipment selection to route planning and crew sizing. Note that the 80,000-pound limit is most often associated with interstate operations and with combinations designed for long-haul work rather than quick on-scene recoveries. The regulatory landscape is nuanced and can allow exceptions, but those exceptions come with permits, route design, and driver qualifications that many operators treat as a formal project rather than routine practice.

Beyond the federal baseline, state and local rules can add restrictions. A configuration permissible in one state might require a permit or be prohibited in another. Tow operators must stay informed about the jurisdiction in use at any moment. For example, a multi-vehicle tow described in industry discourse as a double or triple trailer arrangement requires explicit authorization, specialized equipment, and a carefully planned route. Permits encode strict requirements about vehicle structure, braking performance, load distribution, and the training and licensing of personnel who will execute the tow. Without those measures, the risk of axle failure, brake lock-up, or loss of control increases.

Mechanics and technology also constrain how many vehicles can be hooked up at once. A tow truck’s braking system, steering geometry, and suspension are designed for specific load profiles. Add the towing attachments, couplers, lighting, and signaling, and the margin for error narrows. More vehicles mean greater demands on the drive line, transmission, and braking circuits. Single-vehicle recovery remains common, while larger setups require careful planning, higher equipment standards, and trained crews. The practical takeaway is that the rate-limiting factor is safety and control, not simply the maximum mass on the hook.

In practice, many operators find roadside recovery tasks are best served by a measured approach: one vehicle in many cases, especially when safety under unpredictable traffic, weather, and road surfaces is the core objective. When a situation demands more than one vehicle, procedures become more elaborate: the route and load must be meticulously planned, the permit and equipment must be in place, and signaling and coordination must be precise. The capacity to tow more cars exists in large rigs, but safe and legal ability to do so hinges on permits, equipment standards, and operator competency.

For readers curious about engineering and safety, the literature on tow-truck technology and safety provides practical insights into how crews manage load, braking, and control under pressure. Capacity is therefore context-driven rather than a fixed yardstick. The emphasis remains safety, regulatory compliance, and the recognition that the how-many question really resolves into three questions: How many can be towed legally? How many can be towed safely? And how many should be towed in a given moment to ensure safety for everyone on the road, including the towed vehicles and the crew. For further reading, see official guidance from authorities such as the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/regulations/vehicle-size-and-weight-limits

Weight, Wheels, and Route: How Vehicle Type Sets the Limit on How Many Cars a Tow Truck Can Haul

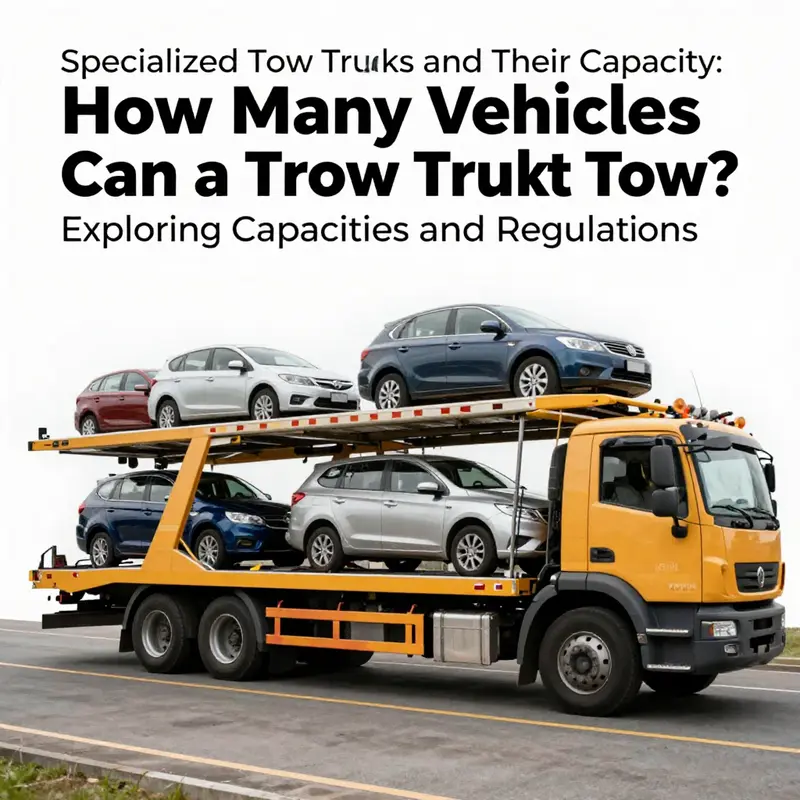

The number of vehicles a tow truck can haul at once is rarely a single, fixed figure. It is a tapestry woven from the type and size of the towing vehicle, the weight and geometry of each towed vehicle, and the conditions of the road on which the operation unfolds. When you peel back the layers, the answer emerges not as a simple arithmetic but as a careful balance of physics, safety, and logistics that varies from job to job. In practical terms, small light-duty tow trucks are designed to move one vehicle at a time, offering nimble handling and quick clarity during roadside recoveries. They excel when the vehicle being recovered is compact or light, where a single unit can lift, stabilize, and transport without overstepping the truck’s rated limits. As the size and weight of the target vehicle grow, the capacity to tow remains constrained by the tug’s own frame, engine power, braking capability, and the geometric constraints of the attachment system. A mid-size, dual-axle unit often handles two or three standard passenger cars when conditions are favorable, provided each car’s curb weight and distribution stay within the truck’s load rating. These trucks typically employ wheel-lift or simple dolly systems that can capture front or rear axles while keeping a reasonable margin of safety. Yet the moment one adds heavier vehicles into the mix—SUVs, light trucks, or commercial vans—the math shifts decisively. Large, high-capacity tow trucks can, under optimal circumstances, tow four to six vehicles if the towed vehicles are small and uniformly light. But this upper limit is rarely realized in the real world because the combined weight, the center of gravity, and the aerodynamics of a column of towed vehicles all come into play. The weight carried by a tow truck is not merely the sum of vehicle masses. It also includes a portion of the trailer or carrier structure, the impact of load distribution across multiple axles, and the dynamic effects of acceleration, braking, and cornering. When the vehicles being towed differ markedly in size, the operator must account for the heaviest end of the chain. For instance, a fleet of sedans and compact crossovers on a single, heavy-duty carrier can be managed more readily than a mixture that includes one or two full-size SUVs or small pickups. In instances where the payload is pushed toward the upper end of the vehicle’s capacity rating, operators shift strategies. They may opt for a flatbed approach, where the disabled car is secured on a stationary platform that minimizes load on the tow vehicle’s drivetrain and suspension. A flatbed can distribute mass more evenly and decouple the weight of the towed vehicle from the towing truck’s axles, which in turn expands the feasible number of towed cars in some configurations. Conversely, the wheel-lift setup shines for light vehicles due to its maneuverability and visibility during transport. It preserves the towed vehicle’s alignment with the road and reduces the distance the tow truck must travel with the towed mass. The choice between these methods is not merely about capacity; it is about preserving control, preventing damage, and ensuring the tow crew can react to changing conditions with precision. The road itself imposes constraints that are easy to overlook in a quiet garage: grade, weather, surface friction, and wind. A steep ascent or a slick descent introduces greater strain on braking systems and amplifies the risk of load shift. Crosswinds can buffet a line of vehicles, magnifying sway and complicating braking. In high-wind or hilly terrain, what would be a manageable four-car operation on a flat, dry highway might quickly become two or even one vehicle if the setup begins to feel unstable. These realities underscore why the “maximum” number cited in catalog pages or training manuals is not a universal truth but a safety threshold that operators must revalidate with every tow. The type and configuration of the vehicles, then, becomes the anchor around which all planning revolves. Vehicle types influence the primary towing method. Wheel-lift systems work best when the weight distribution is favorable and the towed mass remains within manageable limits. For heavier cars or mixed fleets, flatbed tow trucks offer a higher capacity ceiling by stabilizing the load over a larger platform, reducing the risk of tire damage, suspension strain, or accidental shifts during transit. For heavy-duty applications—where the vehicles may exceed standard curb weights or where the goal is long-distance transport rather than a roadside recovery—the use of specialized equipment, and sometimes multiple trucks, becomes necessary. In very rare cases, the industry uses multi-car transport arrangements that can carry eight to twelve passenger cars on two levels. These are specialized, long-distance configurations and are not employed for typical roadside incidents. They demonstrate just how far the concept of “capacity” can be stretched when the objective is continuous, long-haul transport rather than a quick recovery on a constrained public road. Understanding the specifics of each vehicle type—its curb weight, axle configuration, and center of gravity—helps determine the appropriate towing setup. With the wheel-lift approach, knowledge of axle positions and weight distribution guides the operators in deciding how many vehicles can be practically and safely towed in sequence. With flatbed configurations, the same practical considerations apply but are augmented by the stability of a larger platform that spreads the mass over a broader area. In any scenario, the operator must respect safety regulations and legal load limits. These controls are designed not only to protect the towed vehicles but also to preserve the integrity of the tow truck, its attachment points, and the crew handling the operation. It is a discipline that blends technical know-how with on-the-ground judgment, and it is precisely this blend that makes professional towing both a science and an art. When the vehicles involved vary widely in size, a quick, vehicle-specific estimate can be found by considering not only the mass but how that mass interacts with the towing configuration. For readers seeking a concise, vehicle-specific gauge, see How much can my truck tow. The page offers a practical starting point for quick assessments before the more detailed calculations or professional consultation. For a deeper dive into the technical specifications that justify these decisions, the literature offers a more comprehensive guide: https://www.towtrucks.com/used-tow-truck-guide. This external resource expands on wheel-lift versus flatbed principles, the ramifications of different axle configurations, and the regulatory framework that shapes how many vehicles can safely be towed in varying contexts. The overarching message remains consistent: vehicle type is the decisive factor. It sets the baseline for what is physically plausible, what is safe, and what is operationally efficient. The conversation about capacity is not simply about stacking more cars onto a tow bed; it is about pairing the right method with the right mass, the right road, and the right rate of motion. It is about recognizing the limits of the equipment and the realities of the road while keeping the human factor at the center—the driver’s training, the crew’s coordination, and the evolving understanding of how different vehicles behave when they are pulled, pushed, or carried from one point to another. As this chapter has traced, the ability to tow multiple vehicles at once is a function of a chain of decisions: the vehicle types involved, the towing method chosen, the weight distribution achieved, and the road conditions that will govern the journey. The best outcome is achieved when operators assess each element with care, rather than relying on a single rule of thumb. In practice, the number you arrive at will be a carefully reasoned estimate rather than a fixed number you can apply in every situation. The resulting plan will reflect both the limits of the machinery and the responsibilities of the crew to maintain control, preserve safety, and ensure timely, damage-free transport for every vehicle involved.

One Vehicle at a Time: How Tow Trucks Determine Safe Capacity Across Real-World Scenarios

When people ask how many vehicles a tow truck can haul at once, they’re often hoping for a simple numerical answer. In the real world, capacity isn’t a fixed number. It’s a careful calculation that balances the tow unit’s design, the weight and shape of the vehicles involved, the road and weather, and the rules that govern safe roadside recovery. What seems straightforward quickly reveals itself as a nuanced discipline where safety and method trump a desire to maximize the load. The starting point is the type of tow truck itself, because different chassis, beds, and wheel-hifts are built for different purposes. Small, light-duty tow trucks are typically designed for one vehicle, especially if that vehicle is compact or light in weight. Their wheel bases, braking systems, and traction limits simply aren’t sized to carry a second car without compromising control and stability. Move up a notch to medium-sized tow trucks, such as those commonly used for everyday towing in urban centers. In many configurations, these units can tow two or even three standard passenger cars, provided the vehicles are within the truck’s overall weight capacity and the payload is distributed to maintain balance. The equation changes when the cars aren’t typical passenger cars. A high-end sedan set against a heavier SUV, or a commercial vehicle with a substantially different drivetrain, can push the limits of a medium-duty vehicle quickly. Then there are large, heavy-duty tow trucks. These machines are engineered to move more, and in controlled conditions they can tow four to six lighter passenger cars. But even here, the caveat applies: when the towed vehicles are larger, heavier, or less compatible with the truck’s weight distribution, the safe, standard practice can shrink to one vehicle. It’s not simply a matter of raw pulling power; it’s about controlling the whole load as it sits on the road, in motion, and through curves and grades.

In practice, the rule of thumb remains clear: for everyday roadside recovery, a single tow truck handles one vehicle at a time. This principle emphasizes stability, tire and suspension protection, and predictable braking and steering responses. When talk turns to multi-vehicle recoveries, it’s almost always a specialized operation under carefully orchestrated conditions, with highly trained personnel, appropriate payload limits, and repeated safety checks. The public-facing image of a tow truck cradling several vehicles at once often appears in fiction or big-budget media, but the reality on the highway is more conservative. Even the largest on-road tow configurations do not routinely haul multiple cars in a single, unsupervised recovery. Specialized, long-haul transport rigs—such as those designed to move cars over long distances—can stack several cars in a controlled, two-level arrangement. These are not the units you’d call for a roadside jam or a quick lane-clearance; they require planning, permits, and a road segment that’s suitable for multi-vehicle, multi-level transport.

To understand why the number varies so much, it helps to consider the main modes of tow equipment. Flatbed, or rollback, tow trucks are among the safest and most versatile. They carry the entire disabled vehicle on a hydraulically tilting bed, keeping all four tires off the road and reducing the risk of further damage to the vehicle’s drivetrain or suspension. Loading and unloading a car onto a flatbed requires space, time, and careful attention to load alignment, but the payoff is a stable, secure transport that generally allows single-vehicle recovery to minimize risk. Wheel-lift tow trucks, by contrast, are compact and quick to deploy. They lift one end of a vehicle off the ground and drag the rest along. This approach is particularly effective for quick recoveries in tight urban spaces and when time is of the essence. However, the method concentrates stress on the vehicle’s undercarriage and drivetrain during movement, and it has limitations with all-wheel-drive or four-wheel-drive vehicles. Finally, integrated or wrecker-style units pack the towing apparatus into the chassis, offering a stable platform for specific operations where space or terrain constraints demand a different balance between maneuverability and load stability.

These distinctions illuminate a broader truth: capacity is inseparable from safety. A tow operator must constantly weigh how to keep the load centered, how to prevent sway, and how to avoid exceeding the truck’s braking, steering, and tire limits. Road conditions amplify these concerns. A gentle grade on a dry highway may permit a higher load for a routine recovery, while a steep grade, slick surface, or sharp curves demand a much tighter margin. Legal load limits, often set by jurisdiction and reinforced by insurance and carrier policies, add another layer. Even if a truck’s mechanical capability could theoretically allow more vehicles, the law and company policy may restrict operations to one vehicle per tow to limit liability and ensure stable handling in unpredictable real-world conditions.

The not-so-secret nuance is that the general statement—one vehicle at a time—holds across the spectrum of typical roadside situations. When the situation scales up to involve multiple vehicles, the circumstances become atypical: an accident scene with several cars, a controlled relocation of small, light vehicles on a purpose-built transport unit, or a long-distance recovery that uses a dedicated multi-vehicle carrier. In those scenarios, the operation is carefully segmented. A single trip might move one vehicle first, with a precise reconfiguration of the load and a second vehicle moved only after the first is secured for road travel. The idea is not simply to “fit more,” but to preserve safety margins, maintain controlled weight distribution, and ensure each vehicle is secured so that no shifting occurs during transit.

The practical upshot is that the capacity question is almost always answered by a few core factors rather than a single number. First, the truck’s own weight rating and wheelbase shape the ceiling. Second, the weight, size, and drivetrain of the vehicles being towed determine how much mass the truck can carry without compromising steering or braking effectiveness. Third, loading configuration matters: a flatbed can distribute weight differently from a wheel-lift setup, and a combined approach might be used for a special case with strict loading limits. Fourth, external conditions—weather, road surface, wind, and traffic—can rapidly tilt a decision toward the safer option of towing a single vehicle. Fifth, regulatory and insurer guidelines often constrain how many vehicles may be towed in a single operation, further reinforcing the conservative standard.

It’s worth noting a rare but real exception for long-haul transport: double-decker or multi-level trailers can carry eight to twelve passenger cars when used strictly for long-distance moves, not for on-scene, time-critical roadside recovery. These are specialized, highly regulated, and require a different set of permits and escorts; they illustrate that capacity is fluid and purpose-built, not a blanket rule that applies to every tow truck operation. In the context of typical roadside incidents, however, the emphasis remains on one vehicle at a time. This isn’t a discouragement of efficiency; it’s a disciplined approach to safety and reliability that keeps roads safer and recoveries more predictable for all road users.

For readers who want to connect this framework to a practical sense of their own vehicle’s role, consider how weight, balance, and road conditions apply to every tow you might witness or require. If you’re curious about your own vehicle’s tow capability, you can check how much can my truck tow to get a sense of the limits in a real-world context. And while those figures offer a helpful benchmark, the professional operator on the scene will translate them into action, choosing a modality and a load plan that preserves safety first and keeps the recovery efficient and controlled.

Beyond the immediate roadside question, the chapter on specialized tow trucks reminds us that capacity is not simply about maximizing the number of vehicles moved per trip. It’s about selecting the right tool for the job, matching that tool to the vehicle profile, and executing the move with a disciplined approach that prioritizes safety over speed. The result is a consistent standard in which most recoveries proceed with a single vehicle per operation, while recognizing that larger or more complex scenarios demand careful planning, appropriate equipment, and a clear-eyed assessment of risk. The overarching goal remains stable, predictable outcomes that protect people, property, and the road itself—and that is the measure of capacity in the real world, not merely a tally of how many cars can be loaded onto a truck.

External resource: https://www.towtruck.com/technical-overview-best-tow-trucks-specifications-and-applications/

Final thoughts

Ultimately, understanding how many trucks a tow truck can tow is paramount for anyone involved in vehicle recovery or transport. From light-duty tow trucks designed for single vehicle towing to heavy-duty variants capable of multiplexing loads, the capabilities vary significantly based on truck size and vehicle type. Additionally, being aware of local safety regulations ensures that towing operations maintain high safety standards and legal compliance. This knowledge empowers everyday drivers, truck owners, and fleet managers to make informed choices and use towing services more effectively.