Tow trucks are essential for removing disabled vehicles, supporting roadside assistance, and keeping traffic moving. Licensing to operate a tow truck is not always straightforward and depends on several moving parts: the vehicle’s weight (GVWR), how the truck is used (for-hire versus private use), whether hazardous materials are involved, and the state or locality’s DMV guidance. In the United States, heavy-duty tow trucks that exceed 26,001 pounds GVWR commonly trigger CDL requirements, and hauling hazardous materials often requires a CDL with HazMat endorsements. Lighter tow setups may fall under a standard driver’s license, but state rules can vary, especially for commercial operations. The Class A, B, or C CDL designations depend on the combination of tow truck and any trailer. Add in evolving DOT regulations and local enforcement, and the licensing picture becomes highly context-specific. This four-chapter guide connects the dots for Everyday Drivers, Residents & Commuters, Truck Owners, Auto Repair Shops & Dealerships, and Property Managers, illustrating what to know, what to verify with your DMV, and how licensing impacts safety, costs, and operations. Each chapter builds toward a holistic understanding of when a CDL is required for tow-truck work.

Tow Truck CDL Thresholds: Navigating Weight, Rules, and the Legal Path to Driving a Wrecker

The question of whether a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) is required to drive a tow truck sits at the intersection of weight, vehicle configuration, and the legal framework that governs on‑road safety in the United States. For many operators, the answer is clear in the truck’s numbers, but those numbers are not always straightforward. The GVWR, or gross vehicle weight rating, of the tow truck itself, plus the GVWR of any vehicle it intends to tow, creates a kind of weight calculus that determines the license class and, in some cases, whether a CDL is needed at all. The broader rule is simple in structure but nuanced in practice: heavier, more capable combinations tend to demand more credentialing, while lighter setups may fall within non‑commercial licensing. Yet even that simplicity hides the reality that state rules can bend the interpretation of “tow operations” in ways that affect eligibility, endorsements, and the path to becoming a professional tow truck operator.

To start, the weight thresholds that commonly drive CDL requirements sit around a pair of critical numbers: 26,001 pounds and 10,000 pounds. When the tow truck itself has a GVWR greater than 26,000 pounds, and it is towing a vehicle with a GVWR over 10,000 pounds, the licensing framework generally pushes toward a Class A CDL. A Class A license reflects the capacity to operate a combination vehicle with a gross combined weight that exceeds the 26,000‑pound threshold, paired with a towed vehicle that itself surpasses 10,000 pounds. In practical terms, this means a heavy wrecker or a large recovery unit that routinely hauls sizable towed vehicles will almost always require a Class A CDL, because the combination meets the standard for high‑weight operation. The logic here mirrors the general CDL structure beyond tow trucks: when the vehicle and its trailer together form a heavy‑haul arrangement, a Class A license is the default expectation, along with the potential for enhanced endorsements that handle the specific hazards of the cargo or equipment.

If the tow truck exceeds 26,000 pounds but the towed vehicle remains 10,000 pounds or less, the vehicle operator is typically steered toward a Class B CDL. This reflects a distinction between the capacity to pull heavier trailers or heavier towed loads and the practical boundary where the towed vehicle’s weight does not cross the heavier threshold. The Class B scenario is common for larger tow rigs that might tow several smaller cars, light trucks, or utility trailers that stay under 10,000 pounds. The practical effect is that the operator has a license robust enough for heavier on‑road operation but not the combination weight that necessitates Class A.

The landscape grows more nuanced when the tow truck’s GVWR is 26,000 pounds or less. In these cases, a Class C CDL can come into play, depending on other factors defined by the jurisdiction. The most common triggers for Class C in a tow context are twofold: either the vehicle is designed to carry more than 15 passengers (including the driver), or the combination involves towing a vehicle or equipment that weighs more than 10,000 pounds. In other words, a lighter tow truck that nonetheless pulls a heavier trailer or carries more than a dozen passengers a shift could still require a Class C license. This nuance matters because it shifts the emphasis from the tow truck’s own weight to the operational profile of the vehicle—how it’s used, what it carries, and the safety requirements associated with that use.

Among the practical implications for tow operators, the classification matters more than the label itself. In many fleets, a Class A license unlocks the ability to handle heavier wrecking operations, larger recovery rigs, or combinations that involve heavy trailers alongside the tow truck. A Class B license might cover a substantial spectrum of heavy tow work where the towed load stays under the 10,000‑pound line, but the truck itself remains a heavy vehicle. Class C, meanwhile, is a reminder that lighter equipment does not automatically exempt a driver from licensing rules simply because the truck’s weight is under the 26,000‑pound line. If the operation involves a heavier trailer or a high passenger load, Class C becomes the governing credential.

An important caveat that intersects both public policy and practical day‑to‑day work is the prohibition around certain eligibility factors that can affect CDL access. Recent federal guidance strengthens the stance that eligibility is tied to lawful presence and proper identity documentation. In practical terms, this means that the process of obtaining a CDL includes clear legal status prerequisites, medical certification, knowledge and road skill testing, and a structured endorsement pathway for specialized operations. Operators who work in rescue, emergency response, or heavy recovery roles may also require endorsements related to hazardous materials or passenger transport, depending on the mission profile and local rules. The bottom line is that the CDL is not merely a badge of capability; it is a gateway that, if not properly navigated, can restrict who is legally permitted to operate heavier tow configurations or to perform certain kinds of towing work.

Given this complexity, the most reliable way to confirm CDL needs for a specific vehicle and location is to begin with the machine itself. Locate the GVWR on the manufacturer’s plate or the vehicle title, and determine the GVWR of any vehicle you plan to tow. With those figures in hand, apply the general framework described above and then verify with the state’s DMV or transportation authority, because states can add nuances to the definition of “tow operations” and interpret weight thresholds in slightly different ways. The FMCSA offers eligibility tools designed to support drivers and fleet managers in identifying the right license class for a given combination, though the exact online interface may vary by state. Because rules can shift with policy updates, a quick cross‑check with the DMV is a prudent step before you begin driving a tow truck in professional service.

In practice, many heavy wreckers and recovery units are built with robust GVWRs that push toward Class A due to the common pairing of a heavy tow truck with a significantly heavier towed vehicle. Yet there are numerous scenarios where a heavy tow truck might operate a lighter trailer or where a lighter tow truck could be involved in operations that involve heavier towed loads or higher passenger counts, thereby triggering Class B or Class C. To navigate these scenarios successfully, a driver needs to be comfortable with weighing the vehicle and trailer, understanding the classification logic, and recognizing when an endorsement—such as for hazardous materials or passenger transport—might be necessary. Beyond the letter of the law, it is also about safety: the kinds of loads, the complexity of the towing operation, the length of towed configurations, and the risk that comes with heavy recovery work all demand a credentialed operator who has demonstrated competence through the appropriate testing and medical certification.

For fleet operators, the decision tree often starts with a simple audit of equipment and operations. Does the tow truck sit above 26,000 pounds when unloaded? Does the planned towing configuration include a trailer or vehicle exceeding 10,000 pounds in weight? Will the operation involve significant passenger capacity or hazardous materials transport? These questions are not just about compliance; they shape recruitment, training, and the everyday planning of road calls and recovery jobs. In many regions, the fleet’s standard operating procedure (SOP) will specify the required CDL class based on the typical job profile, and this SOP will be supported by a documented process for verifying license status before dispatch. Such practices help prevent violations that could jeopardize a driver’s career, the fleet’s compliance posture, and the safety of the public on the road.

The question of how to confirm CDL needs also invites practical steps that drivers can take. Start with Step 1: locate the GVWR on the tow truck’s plate or registration. Step 2: determine the GVWR of any towed vehicle. Step 3: use the FMCSA Eligibility Tool or the state DMV resources to get a tailored assessment for your exact combination. Step 4: reach out to the state DMV for confirmation, acknowledging that some jurisdictions have unique definitions for what constitutes a “tow operation” or “recovery vehicle” that can influence whether a CDL is necessary. Step 5: if you pursue a CDL, prepare for the process—written knowledge tests, a medical certificate, and a road test—according to your state’s guidelines. These steps transform a theoretical framework into a practical, road‑ready license pathway. In many cases, aspiring tow truck operators also benefit from building familiarity with state specific SOPs, equipment safety standards, and the range of endorsements that might apply to their typical workload. The CDL journey is not merely about passing tests; it is about cultivating the discipline to operate heavy equipment responsibly and to communicate clearly with dispatchers, safety officers, and highway authorities about the vehicle’s capabilities and limitations.

The broader narrative around CDL requirements is not just a checklist; it reflects the essential balance between mobility and safety in roadside assistance. Tow operators often work in dynamic environments, where the weight of a vehicle and the complexity of a recovery can change within minutes. The rules are designed to ensure that the person behind the wheel possesses the experience, training, and judgment to handle those shifts in risk. Hazards associated with tow work—stabilizing a heavy vehicle, securing a damaged frame, and maneuvering in crowded or constrained spaces—demand a licensed professional who has not only mastered the technical aspects of driving but also the regulatory responsibilities that accompany it. In that sense, CDL requirements serve as a framework that protects drivers, other road users, and the people awaiting help on a highway shoulder, an accident scene, or a remote stretch of road.

For readers who want a practical reference that ties these licensing decisions to real‑world practice, a focused resource like the CDL Tow Truck Guide provides a concise map of classifications, endorsements, and typical job profiles. This guide helps translate the general thresholds into the specific configurations that a given operator might encounter on service calls. It’s a useful companion to the regulatory texts, offering scenario‑based explanations that make the rules tangible rather than abstract. See the CDL Tow Truck Guide for a practical overview that aligns with the framework described here.

Beyond the technical rules, the licensing landscape also reflects evolving safety standards and workforce considerations. States may adjust definitions to accommodate new equipment, updated towing practices, or changes in how recovery operations are conducted on busy corridors and at complex accident scenes. Fleets, too, must adapt by investing in training and certification that align with the vehicle types they deploy, the typical loads they encounter, and the regulatory expectations relevant to their region. That alignment is what turns a weight threshold into a reliable operating model. It is why many operators treat the CDL as a critical credential—one that unlocks the range of work they can perform, while also anchoring them in the shared standards that make the broader towing ecosystem safer and more predictable for everyone on the road.

If you are building or refining a towing operation, remember that the licensing decision is not merely about a license plate or a certificate. It is about the right mix of vehicle capability, operator competency, and regulatory compliance that supports timely, safe, and legal roadside response. The process begins with the numbers on the truck and the weight of what you plan to tow, but it ends with a license that confirms you have the training, knowledge, and medical clearance to carry out high‑risk tasks under real‑world conditions. For those seeking a practical starting point and a structured overview that ties weight thresholds to license classes, the linked CDL Tow Truck Guide offers a clear, accessible reference. CDL Tow Truck Guide

As you weigh the options for your own operation, keep in mind that the exact requirements will hinge on your state’s interpretation of the rules and on the specific configurations of your fleet. Always verify with your local DMV, and use the available federal and state resources to triangulate the most accurate path to compliance. When you align the vehicle’s GVWR, the towed vehicle’s GVWR, and the intended use with the proper CDL class and endorsements, you establish a solid foundation for legal operation, professional credibility, and safer road performance. The result is not just compliance in a filing cabinet; it is a practical, on‑the‑ground capability that enables you to respond to emergencies and breakdowns with confidence, competence, and accountability. For readers who want to explore the federal context that shapes these rules, consult official regulatory resources from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration for broader guidance and updates on licensing, vehicle classifications, and safety standards.

External resource: For official federal guidance, see the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s licensing and safety information at https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/.

The CDL Question for Tow Trucks: Weighing GVWR, HazMat, and the Endorsement Path

For tow-truck operators, the question of whether a commercial driver’s license is required is rarely a simple yes-or-no call. It hinges on the vehicle’s weight, the configuration of the truck and trailer, and the nature of the loads you haul or tow. In the United States, the most consistent rule across many jurisdictions is that a CDL is required if the tow truck, alone or in combination with any trailers, would push the vehicle’s gross vehicle weight rating beyond a threshold. That threshold, commonly stated as over 26,000 pounds GVWR, becomes the deciding line that moves a job from standard license territory into commercial licensing territory. From there, the exact class of CDL—Class A, Class B, or Class C—depends on how you operate the vehicle and what you tow. Add in the possibility of carrying hazardous materials and the requirement can shift dramatically and quickly, even if the tow truck itself sits just below the weight line. This is not merely a bureaucratic hurdle; it is a framework designed to reflect the risks involved in operating heavy, sometimes complex equipment on public roadways, and to ensure that anyone in the field has demonstrated the knowledge, skills, and reliability necessary to perform under demanding conditions.

Think of the GVWR as the first gatekeeper. Tow trucks are built in many shapes and sizes, from compact wreckers designed to pin down a stalled vehicle to heavy-duty rotators with multiple winches, hydraulic lines, and payload capabilities that can feel almost formidable when loaded. When a vehicle’s GVWR exceeds 26,000 pounds, many states require a CDL, with the exact class dependent on the total weight when you couple a tow truck with a trailer or with any other trailing equipment. The rule is straightforward in principle, but real-world applications can vary. A tow truck with a GVWR of 27,000 pounds paired with a small trailer may require Class B, while the same chassis operating with a more substantial trailer could trigger Class A requirements due to the combined weight. In practice, this means the operator and the company must map out the fleet’s configurations, the nature of towing operations, and the specific state rules that apply where service is rendered. To understand how a given truck fits into the licensing framework, the key is to determine the GVWR and to consider how any attached equipment or trailers changes the total weight.

The HazMat layer introduces another, equally important dimension. HazMat regulations do not automatically convert every tow-truck driver into a HazMat specialist. Rather, the endorsement becomes necessary when the job involves transporting hazardous materials as part of the duties. If the vehicle itself or the operational scenario includes loads like fuels, solvents, or other regulated chemicals, the HazMat endorsement steps into the picture. The rule is subtle but critical: you don’t obtain HazMat simply by driving a tow truck; you earn it by transporting hazardous materials as part of the work you perform. That means you could tow in certain contexts without HazMat, while other jobs—such as towing a vehicle that is legally carrying hazardous materials, or transporting a load that is hazardous in nature—trigger the need for HazMat certification.

For many operators, the practical question becomes not just whether they will ever transport HazMat, but whether they might in the future, and whether they want the flexibility that endorsements provide. The endorsement path typically begins with a separate knowledge test focusing on HazMat material, but it does not stop there. Because HazMat regulations have security and safety implications, many jurisdictions require background checks and fingerprinting, and in the United States, a good portion of that process is handled through federal channels such as the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). The result is a robust set of steps designed to verify a driver’s trustworthiness and readiness to handle sensitive information and hazardous cargo. In addition to HazMat, there are other endorsements that can become relevant depending on the loads and the vehicle combination. Tanker endorsements, for example, come into play if the job involves transporting liquids in bulk. The situation can feel intricate, but it is precisely this structure that helps ensure safety on the road and protection for the public when tow operations involve heavier equipment, unusual configurations, or hazardous materials.

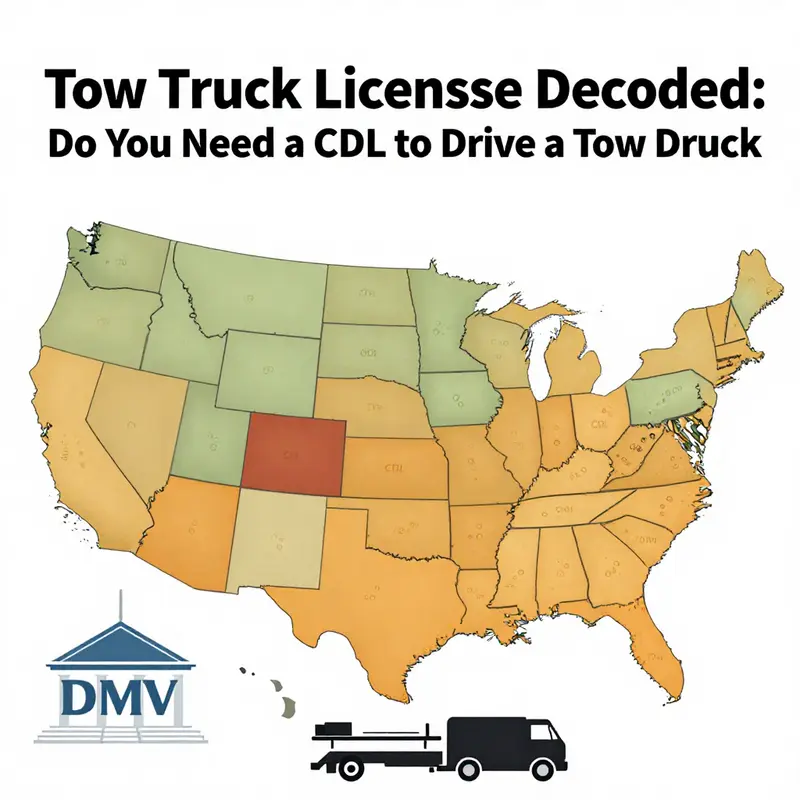

The practical implications of these rules become clearer when you zoom in on state-by-state variability. The federal framework provides broad guardrails—weight-based CDL requirements, HazMat endorsement rules, testing and background checks—but states can layer on their own nuances. Some states align closely with federal definitions and testing criteria, while others add specific endorsements, local testing requirements, or different medical standards. Because road operations cross state lines, a tow-truck operator may encounter different requirements depending on where the job takes them. The truth is that the most comfortable path forward is to consult the local DMV or equivalent agency, study the state manual sections that cover Tow Truck Driver Endorsements, and verify how the combined weight and the cargo type interplay with the licensing requirements. The goal is not to trap the operator in red tape but to ensure that every vehicle on the road carries appropriate credentials for its design and purpose, and that drivers are prepared to manage safety-critical tasks—such as securing a heavy vehicle after a rollover, coordinating with other responders, or safely loading and unloading hazardous materials when required.

In the broader regulatory framework, federal rules continue to govern HazMat transport and endorsement standards, and state implementations may add steps like background checks, medical fitness evaluations, and periodic renewals. Keeping abreast of these developments is essential for fleet managers and solo operators alike, because renewal cycles, testing requirements, and the scope of permissible loads can shift with changes in federal or state law. The chapter here does not aim to replace official manuals or DMV advisories; it offers a synthesis to help readers map out their own course of action. A disciplined approach starts with a clear determination of the tow truck’s GVWR, an honest assessment of what loads you will or might transport, and a plan to pursue endorsements if your work could cross any HazMat boundary. If you are unsure about how a particular vehicle or operation is classified, the safest move is to check directly with the state DMV and request the exact section that applies to tow-truck operations. Official manuals will provide the precise language for vehicle classifications, endorsement requirements, testing prerequisites, and any special considerations that apply to tow trucks in your jurisdiction.

For operators seeking practical context, consider consulting a consolidated guide that focuses on the realities of towing work and licensing. A concise reference sometimes used in the field frames the issue as a three-part decision: assess the vehicle’s GVWR, determine whether hazardous materials are involved, and verify the appropriate CDL class based on the configuration of the tow truck and any trailers. The weight thresholds are not arbitrary; they reflect the capacity of the vehicle to maneuver safely, the stopping distance required for heavy combinations, and the training necessary to manage complex equipment under demanding conditions. A driver who understands these elements is better prepared to navigate incidents on the roadside, coordinate with other responders, and perform tasks such as securing loads, managing traffic scenes, and executing safe recovery operations.

Within this broader landscape, it is worth noting a practical, accessible resource that many readers find helpful for aligning their aspirations with real-world requirements. The CDL Tow Truck Guide provides a structured overview of the licensing landscape as it relates to tow trucks. It breaks down the weight thresholds, the endorsement options, and the steps to obtain HazMat certification in a way that complements state manuals. You can explore this guide as a practical companion when planning your licensing path and evaluating whether your fleet needs Class A or Class B endorsements based on actual configurations. CDL Tow Truck Guide

Beyond the weight and endorsement considerations, professional readiness remains central. Even if a vehicle currently sits under the GVWR threshold, you might operate in a context where you occasionally load equipment or tow trailers that push the overall weight beyond the threshold. In those cases, a CDL becomes prudent not only to comply with the law but to maintain operational flexibility. The broader job sometimes involves responding to emergencies, coordinating with police or fire services, and working in hazardous environments. A CDL can provide the training and accountability needed to handle these pressures responsibly. On the other hand, if your daily operations consistently involve light-duty towing and you never couple a trailer or carry heavy loads, a standard non-commercial license can be sufficient in some states. Yet this simplified path requires diligence; you must verify with your state that this approach aligns with current rules, because the line between commercial and non-commercial operation can blur under certain circumstances, especially with company policies that involve on-call responses or multiple vehicles.

For fleets and individuals who want a clear road map, the practical steps to ensure compliance are straightforward and doable. Start by confirming the GVWR of every tow truck in your fleet. If a vehicle is over 26,000 pounds, you will likely need a CDL, and the class required will depend on the specific vehicle configuration and whether you tow trailers. If your operations involve transporting hazardous materials, plan to pursue HazMat endorsement and prepare for the associated background checks and tests. If you anticipate or require tanker loads or other specialized cargos, consider additional endorsements such as Tanker, and consult state-specific rules to confirm the precise requirements for your jurisdiction.

Next, dig into your state’s DMV or equivalent agency resources. Review the relevant sections of the driver manual, focus on sections that discuss Tow Truck Driver Endorsements and HazMat, and note any special considerations forTow trucks in your state. Look for official section numbers, required tests, medical qualifications, and renewal timelines. When possible, cross-check federal regulations—particularly 49 CFR parts related to HazMat—with your state rules to understand the alignment and any deviations in local practice. This diligence will save time and prevent licensing gaps that could disrupt service or trigger penalties.

As you plan and prepare, remember that the licensing landscape is designed to promote safety and accountability in high-stakes road work. The most effective approach blends a clear understanding of vehicle weight, an honest appraisal of loads and routes, and proactive engagement with licensing authorities. It also means staying current with changes in regulations, which can arise from updates to federal rules or state amendments that reflect evolving safety priorities. Keeping your credentials aligned with the actual operations of your fleet helps ensure you can respond to emergencies confidently, while also maintaining compliance that protects your drivers, your company, and the public.

In terms of how this chapter connects with the surrounding discussion, the core idea is about translating the broad regulatory framework into practical, on-the-ground decisions. The weight-based CDL threshold, the HazMat endorsement pathway, and the realities of state-by-state variation converge to shape a driver’s qualification profile. For some, this means pursuing a straightforward Class B or Class A license, with HazMat added if the job scope warrants it. For others, it suggests maintaining a non-commercial license with the knowledge that certain operations may compel a conversion to a CDL later if fleet expansion or service requirements evolve. Either pathway requires a careful audit of the equipment in use, the typical loads encountered, and the legal obligations that apply to the work site and the road network. The objective is not merely compliance in a legal sense, but the assurance that every tow operation can be conducted safely, efficiently, and with the confidence that comes from being fully credentialed for the task at hand.

If you want a concise, practical starting point, begin by verifying the GVWR of your heaviest tow unit and any trailers. Then map out whether HazMat or Tanker endorsements would add value to your operations. From there, consult your state DMV manuals and, when possible, reference a credible guide like the CDL Tow Truck Guide to align your licensing plan with real-world requirements. That approach makes it easier to plan for training, scheduling tests, and budgeting for fees. It also helps avoid the risk of being over- or under-credentialed, ensuring you can take on the widest range of calls while staying within the law. The path to a compliant, capable tow-truck operation is not a single step, but a series of reachable steps that build a driver’s credentials in step with the evolving demands of the job.

External resource for further reading: For authoritative guidance on HazMat and CDL endorsements, the New York State DMV provides detailed manuals and procedures, which can help illustrate how the endorsements are implemented in a real-state context. You can review the official Tow Truck Driver’s Endorsement guidance here: https://dmv.ny.gov/permits/tdm.pdf

Tow Trucks and the CDL Question: Navigating Weight Thresholds, State Rules, and DMV Guidance

When a tow operator steps into the rig, the pressing question about a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) often surfaces long before the first call comes in. The answer is not a simple yes or no. It is a layered assessment rooted in the vehicle’s weight, its configuration, and the state where the work will occur. This complexity matters because it shapes who can legally drive the tow truck, what kind of license they need, and how much training or testing stands between the operator and a dispatch job. In practical terms, the CDL decision is a hinge that can unlock or restrict a tow business’s capabilities, access to customers, and, more importantly, safety and compliance on the road. The road to clarity begins with the basics: weight thresholds and the kind of hauling the truck is built to perform.

The most widely cited rule in the United States ties CDL necessity to the vehicle’s Gross Vehicle Weight Rating, or GVWR. When the GVWR is 26,001 pounds or more, a CDL is typically required. This threshold covers many heavy-duty tow trucks, especially those designed to haul multiple vehicles, heavy loads, or large payloads. The logic is straightforward: heavier vehicles demand stricter operator qualifications, higher skill levels, and more rigorous safety oversight. A tow truck designed to lift and tow a car or two and manage roadside recoveries often sits at or above that line, particularly if it pairs with a towable trailer. But a truck slimmed down to handle lighter tows—or a wheel-lift setup that doesn’t routinely haul heavy vehicles—may fall under the threshold and run on a standard, non-commercial license in some states. The nuance here is crucial. The same truck could be treated differently depending on the state and the specific use case, which means the practice of licensing is as much a matter of jurisdiction as it is of technology.

Beyond the weight that appears on a spec sheet, there is the transporter of hazardous materials to consider. If the tow operation involves moving hazardous materials—think fuels, solvents, solvents stored in the vehicle’s compartments, or chemicals—the CDL rule becomes stricter, often mandating a CDL regardless of the GVWR. Hazardous materials endorsements or separate CDL categories can come into play, adding layers of training, testing, and compliance requirements. This is not merely an extra credential; it is a safety and regulatory safeguard intended to minimize risk on routes that intersect with fuel depots, maintenance yards, and busy highways where the stakes are particularly high. In short, when hazardous materials are part of the job, the licensing path tightens, and the decision about which class of CDL is necessary becomes more explicit.

But even within the broad federal framework, the state plays a decisive hand. For lighter tow trucks—those under 26,001 pounds—the path can vary from one state to another. Some states permit operation with a standard driver’s license if the work is purely non-commercial or does not involve extensive hauling beyond a defined payload. Other states, however, apply commercial use tests more aggressively, requiring a CDL or a permit for any business-related tow activity, even if the GVWR sits just under the threshold. The result is a patchwork of rules that operators must navigate with care, especially if a business operates across state lines or serves customers from multiple jurisdictions. The federal rulebook establishes a baseline, but states can—and do—draw sharper lines to reflect local road safety concerns, enforcement priorities, and economic considerations.

Understanding which Class of CDL applies adds another layer of consideration. A Class A CDL is typically required when the combination of tow truck and trailer exceeds specific weight thresholds. A Class B license covers heavy straight vehicles, while Class C is often associated with smaller vehicles or certain configurations that nonetheless involve the transport of hazardous materials or specialized operations. The key takeaway is that a tow truck might require one of these licenses depending on the combination of vehicle, trailer, and intended use. For instance, a heavy tow truck pulling a sizeable trailer with multiple vehicles could push the operation into Class A territory, while a standalone heavy tow truck without a trailing unit might fall under Class B. These distinctions matter not only for legal compliance but also for insurance, driver training requirements, and the ability to perform certain kinds of towing work.

The conversation around CDL eligibility is further shaped by federal and state interplay. The federal framework, codified in national transportation statutes, provides the overarching structure. States, however, retain substantial authority to tailor the rules to their road networks and enforcement priorities. In practice, this means a driver who is compliant in one state may face a different license requirement if they cross into another state with a different interpretation of the same weight and use. The evolution of this landscape is ongoing, with updates that reflect changes in vehicle technology, fleet operations, and road safety research. Operators who want to stay compliant must treat licensing as a dynamic component of their business—one that benefits from proactive checks rather than reactive fixes after a stop by a highway patrol officer or a DMV examiner.

Given this complexity, the most reliable path to compliance is a direct conversation with the state’s department of motor vehicles (DMV) or its equivalent. DMV guidelines are the primary source for determining whether a particular tow truck—and the job it performs—falls under CDL requirements. Each state’s DMV site typically offers a set of tools or decision trees that walk a driver through questions about GVWR, towing configurations, and whether hazardous materials are involved. The beauty of these tools is that they translate the abstract into practical steps: measure the GVWR, confirm whether a trailer is involved, check if the operation includes hazardous materials, and then verify which CDL class, if any, applies. This is the moment when the theory meets the road, and where many operators learn to calibrate their operations to stay within legal and safe boundaries.

For operators who want a concise resource that translates the rules into a practical guide, a dedicated CDL tow truck guide can be an invaluable companion. It distills state-by-state variations into a usable framework while highlighting common pitfalls that tend to trip drivers up. When you consult such a guide, you gain a clearer sense of what to provide to your dispatch team, what to request from clients, and what to document in your training and compliance files. The guide serves not as a substitute for the DMV, but as a practical planning tool that helps a business prepare for licensing, endorsement needs, and ongoing compliance. If you are exploring this path, you can refer to a resource like CDL-tow-truck-guide, which aggregates essential considerations and links to state-specific guidance. This kind of resource supports a proactive approach rather than reactive licensing, helping a tow operation align with regulatory expectations before the first tow arrives.

While the licensing question is central, it is only one piece of the compliance puzzle. A well-run tow operation keeps track of additional regulatory obligations that influence licensing and daily practice. Medical certification is a standard requirement for many CDL holders, ensuring drivers meet health standards that support long hours, demanding physical tasks, and the stresses of roadside work. Vehicle inspections, record-keeping, and periodic retesting are routine expectations that help ensure a consistent safety baseline across a fleet. Hours-of-service rules, which govern how long a driver may operate without rest, can also shape a tow business, especially for operators who are on-call around the clock to respond to incidents or roadside breakdowns. Insurance requirements ride alongside licensing, with coverage levels and endorsements often contingent on the license class and the vehicle-trailer combination. In short, obtaining a CDL is not merely about meeting a licensing hurdle; it is a gateway to certain categorically permissible work, a framework for training and safety, and a marker of professional readiness for more demanding assignments.

The practical takeaway for someone evaluating CDL needs begins with a careful, methodical review of the specific vehicle and use case. Start with the GVWR on the tow truck. If the number is 26,001 pounds or more, you can reasonably anticipate that a CDL will be required, but confirm this through your state DMV’s official guidance. If hazardous materials are involved, assume a CDL is necessary, and prepare for the appropriate endorsement and training prerequisites. If the GVWR is below the threshold, don’t assume you’re automatically in the clear. State rules can create exemptions or additional constraints based on truck configuration or commercial usage. With this in mind, the next step is to consult the DMV’s official resources and, when needed, seek direct confirmation through a licensed professional or a DMV specialist who can interpret the specifics of your case. The goal is to prevent a misstep that could lead to fines, impoundment, or the need to relicense after a job is underway. For a direct, practical reference, you may consult a resource that specifically addresses CDL for tow trucks: CDL-tow-truck-guide.

All of this emphasizes a broader truth: licensing is not a one-time hurdle but an ongoing management task for a towing business. State laws change, fleet configurations evolve, and new safety standards emerge. A fleet supervisor should periodically re-check the GVWR classifications of each truck in the lineup, review any changes in escort or towing configurations, and stay alert to any updates in state or federal regulations. Keeping operational practices aligned with the latest guidance minimizes disruption to service, protects drivers, and supports a safer road environment for everyone. It also helps create a more predictable workflow for dispatchers and customers, since license and endorsement needs will be clearly understood before a job is accepted. This forward-facing approach is essential for small operators growing into larger fleets, and for companies that aim to unify compliance across multiple jurisdictions.

The right approach thus blends clear mechanical understanding with disciplined regulatory awareness. It requires a willingness to dive into state-by-state guidance while recognizing that the federal framework provides the surrounding structure. For many readers, the practical payoff is a clearer roadmap: identify the truck’s GVWR, map the job’s hauling configuration, assess whether hazardous materials might be involved, and then verify CDL requirements with the state DMV. In the end, the decision becomes less about fear of penalties and more about confidence in safety, legality, and reliability. A tow operation that treats licensing as a strategic part of its operations—rather than as a reactive checkbox—stands a better chance of delivering high-quality service, maintaining good standing with regulators, and building trust with customers who rely on timely, compliant, and professional roadside assistance.

For readers seeking a concrete, state-focused starting point, the California example illustrates how a DMV might present CDL requirements for commercial towing. California’s guidance, like other states’, emphasizes that commercial transport definitions and weight-based thresholds determine whether a CDL is needed. It is a reminder that even if a truck is technically capable of the work, the regulatory framework will define whether a license is required, and which class or endorsement is appropriate. As you work through the specifics of your fleet, remember that the path to compliance is not a single document but a living process that involves regular checks, updates, and reminders to stay current with changes in law and practice. And when in doubt, lean on the DMV’s official guidance and the targeted CDL tow-truck resources that translate the law into practical steps for drivers and fleet managers. The aim is not merely to avoid penalties but to support safer operations, better service, and a workforce that can meet the demands of the road with confidence.

External resource: For additional state-specific context and official guidance, see California DMV – Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) Information. This external reference can offer a concrete example of how one state structures its CDL requirements for commercial towing operations. https://www.dmv.ca.gov/portal/driver-licensing/commercial-drivers-license/

External link note: The chapter concludes with an emphasis on verifying requirements through your local DMV and using state resources as the primary source of truth. As regulations evolve, ongoing review becomes a competitive advantage for operators who want to maintain compliance, safety, and reliability across a diversified set of towing tasks. Regular checks help ensure your crew holds the proper license class, endorsements, and medical certification where applicable, enabling them to handle a wider range of jobs with fewer last-minute licensing surprises. The road to compliant towing is not a single decision but a sequence of informed choices, each anchored in the vehicle’s weight, its use, and the jurisdiction in which it operates.

Tow Truck CDL Realities: Weighing the Need, Endorsements, and Regulatory Boundaries

The question of whether a CDL is required to operate a tow truck is more nuanced than it first appears. In practice, it depends on weight, configuration, and the cargo being moved. In the United States, the upper threshold for a single vehicle is around 26,001 pounds GVWR; once you combine a tow truck with a trailer or with a towed vehicle, the classification can change to a heavier category.

Heavy wreckers, flatbeds, and most long-wheelbase tows commonly push operators into Class A territory, which typically requires a Class A CDL and may carry additional endorsements. Lighter tow trucks under 26,001 pounds GVWR may not automatically require a CDL, but states and specific operations can impose CDL requirements for certain tasks or routes.

Endorsements matter: a hazardous materials endorsement may be needed if fuel or other hazardous cargo is transported; the additional endorsements travel with the license. The exact license class depends on the combination of vehicle and trailer and any specialized equipment that can affect handling.

Beyond the license class, the medical certificate and hours-of-service rules add ongoing compliance. CDL holders must meet medical standards and keep certificates current; many operations require DOT medical certification renewed periodically. This ongoing layer shapes daily routines, pre-trip inspections, and record-keeping.

Regulatory landscapes differ by state. The federal baseline sets core rules, but states may tighten thresholds, endorsements, or training requirements. A tow operator that crosses state lines or serves multiple counties should verify local rules before assigning drivers to a given job.

Practical guidance: pursue the appropriate CDL with the necessary endorsements, such as the tow endorsement where applicable; enroll in a training program that covers recovery procedures and load securement; maintain a robust DOT medical certification; and keep up with regulatory changes through ongoing safety training. Invest in maintenance and documentation to minimize risk and penalties.

Bottom line: a CDL is often the gateway to heavier, more capable tow operations, but the exact requirements hinge on what you plan to tow, where you operate, and how you structure your fleet. The goal is to balance legal compliance with practical capabilities to deliver safe and timely service.

Final thoughts

The CDL landscape for tow trucks is not one-size-fits-all. Weight, how the vehicle is used, and where you operate drive the licensing decision. Heavier tow trucks commonly require a CDL, and hazmat transport adds another layer of endorsement requirements. State rules vary, and ongoing medical and safety compliance is part of everyday operations for fleets and shops. For Everyday Drivers, residents, and property managers, this means confirming the correct license category before dispatching or contracting towing services. For Truck Owners and Auto Repair Shops, factor in training, insurance, and regulatory costs as you scale or professionalize your tow operations. The core takeaway: verify your specific vehicle configuration and jurisdiction with the local DMV, plan for endorsements if needed, and invest in safety and compliance to keep tow operations smooth, legal, and safe.