Tow trucks are a critical part of roadway safety and mobility, but the question of whether you need a commercial driver’s license (CDL) to operate one is more nuanced than shop posters suggest. Federal rules set a baseline—the gross combined weight rating (GCWR) of the tow truck plus the towed vehicle—and many states layer on additional requirements, endorsements, and use-case rules. For everyday drivers and fleet operators alike, understanding these thresholds helps prevent fines, ensures compliance, and supports safer, more predictable operations. This article unpacks the federal framework, surveys state variations, dives into the practicalities of towing hardware and weight calculations, and considers broader industry and public-safety implications. Each chapter builds toward a practical takeaway: whether your tow operation is personal, commercial, or part of a larger organization, knowing when a CDL is required helps you plan, budget, and schedule with confidence.

Tow Truck Licensing and the 26,001-Pound Question: Unraveling Federal Thresholds, State Variations, and Real-World Implications

When people first ask whether a CDL is required to drive a tow truck, the honest answer is: it depends. The simple line on many job boards or training guides can be misleading because licensing isn’t determined solely by the weight of the tow truck itself. It hinges on the combined weight the vehicle is allowed to handle in operation—the Gross Combined Weight Rating, or GCWR. The federal rule, as interpreted and enforced by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA), states that a CDL is required when the GCWR of the tow truck and the towed vehicle, taken together, exceeds 26,001 pounds. This rule travels with the vehicle across state lines, but it doesn’t always map perfectly onto every local situation. The threshold is a compass, not a single lock. It points you toward the correct licensing pathway, but the actual steps to comply depend on the exact weights involved and on the regulations laid out by the state in which you operate or intend to operate.\n\nTo grasp why the GCWR figure is so central, it helps to untangle the weight concepts a bit. The GCWR is not simply the weight limit of the tow truck alone; it is a rating that reflects how much weight the combination—the tow truck plus the vehicle it is towing—can safely handle together. On paper, a tow truck might have a relatively modest curb weight, say under 26,000 pounds. If that truck then tows a vehicle that weighs more than 0 pounds but pushes the total to surpass 26,001 pounds, the federal rule applies. Conversely, a heavier tow truck on its own does not automatically trigger a CDL if the towed load keeps the GCWR at or below 26,001 pounds. This nuance matters because tow operators often deal with a broad spectrum of vehicles—from compact cars to heavy recovery units. The moment the scale tips over 26,001 pounds in combined rating, the CDL becomes the legal baseline for operation in interstate commerce and, in many contexts, for operation within state lines as well.\n\nThe practical consequence of this rule is that a tow truck operator’s licensing needs can shift with the job. A light-duty tugger that tows smaller cars may be able to operate with a standard non-commercial license in some states, particularly for private, non-commercial use. But once the operator starts moving heavier vehicles or operates under a business model that crosses state lines, the GCWR threshold can push the license into the CDL territory. The federal standard is clear, but states don’t always align perfectly with it. Some states may interpret or enforce their rules in ways that are stricter than the federal baseline. That means two operators in neighboring states could briefly be treated differently, depending on the precise weight configuration of their equipment and the state’s own licensing framework. The safest approach is to verify both federal guidelines and the specific state laws where the work will take place. DMV divisions, licensing bureaus, and the FMCSA’s own guidance are the reliable map through this maze.\n\nThis is where the conversation about license classes often becomes essential. In the United States, CDL classifications are not one-size-fits-all. Class A, Class B, and the sometimes-particular state adaptations determine what kind of truck you can drive and in what circumstances. If your tow operation involves a combination vehicle whose GCWR exceeds 26,001 pounds and the towed vehicle has a substantial weight, Class A CDL requirements commonly apply. In many cases, when the towed vehicle’s weight is lighter, a Class B license might suffice for the truck itself, though the combined rating can still pull the operator into CDL territory. The difference isn’t just about the mass; it’s about how that mass is connected and how the vehicle is intended to be used in commerce. It’s a seam where weight, function, and geography intersect. The mapping of the exact classes to individual tow setups is defined in state licensing guides and reinforced by federal standards, which together form the framework that operators must follow.\n\nBeyond the basic license class, many states still require or strongly encourage endorsements for specific towing tasks. The most commonly referenced is the endorsement for towing operations, sometimes labeled as a “T” endorsement in state manuals. The presence of a T endorsement signals that the driver has demonstrated the government-required knowledge and skills related to towing procedures, coupling and uncoupling trailers, safety protocols around heavy towed loads, shutdown and recovery safety, and the proper handling of capabilities and limitations of a tow setup. The federal system does not automatically grant this endorsement; it is earned through a combination of testing and, in some jurisdictions, additional training or experience. In practice, operators who work in commercial towing fleets or who perform heavy-duty recoveries frequently pursue this endorsement to ensure compliance and to signal readiness to clients and insurers. It’s a reminder that licensing is not just about operating the vehicle; it’s about operating it with the appropriate authority and with the proper safety discipline that the job demands.\n\nAnother layer to consider is the line between private usage and commercial operation. The GCWR rule is a federal standard, and it applies regardless of whether the tow is conducted for compensation or as a personal service. However, commercial towing involves additional layers of regulation, insurance, safety training, and hours-of-service considerations if the operation crosses state lines or qualifies as interstate commerce. Those who drive tow trucks as part of legitimate businesses, routine recoveries, or fleet operations are more likely to encounter CDL requirements, because their activities tend to align with the structured oversight that accompanies commercial transport. Private, non-commercial tows—such as helping a friend move a vehicle in a non-business context—often fall outside these strict licensing lines, though state rules can still impose limits or require a CDL for certain heavy towed weights in private operations. The reminder here is simple: you should never assume a license status without confirming the applicable rules in your jurisdiction and for your intended work. The weight numbers don’t lie, but how they are interpreted and enforced can differ by state.\n\nIn addition to the weight thresholds and endorsements, there is the practical matter of training and safety culture. Licensing sets the legal baseline, but the job demands more than a piece of paper. Tow operators must understand rigging, proper hitching, load securement, risk assessment, and incident response. The physiology of heavy equipment—stresses on hydraulics, braking dynamics of a tow setup, and safe practices for working around traffic and on unstable terrain—requires ongoing discipline. Many employers emphasize comprehensive safety training as part of onboarding, and some jurisdictions require periodic refresher courses or specific certifications beyond the CDL, especially for operators who handle complex or dangerous scenes. The law, the insurer, and the fleet safety culture all converge on the same principle: a driver can legally operate a vehicle, but to do so safely and reliably in the most demanding towing scenarios, a prepared professional is essential. This is why even when the GCWR allows for non-CDL operation in some contexts, many operators opt for CDL eligibility not just for compliance but for broader career flexibility and safer practice.\n\nFor individuals navigating this landscape, the recommended path is straightforward yet meticulous. Start with the weights of your equipment: the tow truck’s own GVWR and its GCWR, plus the GVWR of the vehicle you will tow. Add those together, and you will see where you stand relative to the federal 26,001-pound line. Then check the state DMV or licensing authority to understand any stricter thresholds or additional endorsements that may apply to commercial towing within that state. If the GCWR pushes you over the line or if the nature of your work makes it commercially oriented, prepare to pursue a CDL, and specifically, assess which class best matches your combination and the eventual types of towing you plan to perform. If your state requires a T endorsement for towing, factor in the additional testing or training as part of your licensing timeline. It’s a process that rewards careful preparation and clear documentation, because the penalties for misclassification are not limited to a single citation: they can affect insurance rates, fleet credentials, and even the capacity to substitute a licensed operator when the workload demands it.\n\nAs the weight thresholds and licensing paths become clear, the broader picture emerges: the 26,001-pound rule is not just a number; it is a gateway to ensuring safety, accountability, and consistency in a profession that routinely confronts unpredictable roads, dynamic scenes, and heavy loads. The rule is intended to balance the needs of drivers and the public by ensuring that those in charge of heavy, potentially dangerous combinations possess the appropriate training and regulatory coverage. Yet it is also a reminder that every towing scenario has its own fingerprint—the specific mix of equipment, the manner in which the load is secured, and the commercial context in which the work occurs. By approaching licensing with a methodical eye on GCWR, state nuances, and the necessary endorsements, operators can navigate the system with confidence rather than guesswork. They can plan, train, and certify themselves for the precise operations they expect to perform, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all assumption.\n\nFor anyone contemplating a career in towing or expanding a current operation, the message is consistent and practical: determine the weights, verify the rules at both federal and state levels, and align your licensing with the work you actually intend to do. The numbers aren’t merely regulatory scaffolding; they are the backbone of a safe, professional practice that serves communities in their moments of need. The path may require time, effort, and some careful paperwork, but the payoff is a license that matches the job’s demands, a credential that supports career mobility, and, most importantly, a framework that keeps operators and the public safer on every stretch of road.\n\nExternal resource: For detailed federal guidelines on Commercial Driver Licenses and the 26,001-pound threshold, see the FMCSA CDL requirements page: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/regulations/vehicle-requirements/commercial-driver-licenses

Weight, Endorsements, and the CDL Question: Navigating Tow-Truck Licensing Across States

Licensing a tow truck driver isn’t a simple yes-or-no decision. The rules bend with the weight of the equipment, the vehicle being towed, and the state where the work happens. For many operators, the central hinge is the gross combination weight rating (GCWR) of the tow truck and the towed vehicle. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) sets a clear line: if that combined weight exceeds 26,001 pounds, a commercial driver’s license (CDL) is required. It matters even if the tow truck itself weighs far less than 26,001 pounds—the critical figure is the total weight being moved and the potential for highway speeds, long hauls, and the commercial context in which the work occurs. In practice, this means a light-duty tow truck used only for small, private-to-private towing tasks might fall under non-CDL rules in some jurisdictions. But once the weight crosses that threshold, or if the operation expands into interstate commerce, the CDL becomes non-negotiable. The distinction can feel subtle, but it governs certification, training, and the liability that comes with moving heavy vehicles on public roads.

Beyond the federal threshold, state regulators layer on their own rules. Many states mirror the GCWR standard from FMCSA, yet several add twists: some require a CDL for tow trucks used in commercial towing services or for specific classes of tow trucks. Others enforce weight-based distinctions that differ from the federal line by a few hundred pounds, or they demand certain endorsements that signal specialized knowledge. A tow operator who crosses state lines or operates under a business license in multiple jurisdictions will quickly learn that a one-size-fits-all answer doesn’t exist. In practical terms, this means checking both the federal framework and the relevant state DMV regulations for the exact vehicle and operation at hand. The DMV website in each state becomes a critical resource, as it translates the broad federal rule into the local paperwork, tests, and endorsements you’ll actually encounter in day-to-day work.

A useful way to visualize the decision is by walking through a simple truth test. Imagine a tow truck rated to tow a certain maximum weight, paired with a vehicle that you might be called to recover or tow. If the combined GCWR exceeds 26,001 pounds, the operator generally needs a CDL. It does not automatically grant a pass for every operation under that weight; the context matters. If the work is interstate, many state rules defer to the federal standard for CDL applicability and add the possibility of needing additional endorsements. If the operation stays entirely within a single state, some regulators allow non-CDL operation under specific circumstances, provided the weight and usage stay within defined limits. This nuance can cause real confusion on the ground because two drivers with the same tow truck in different contexts might face different licensing requirements.

The licensing landscape becomes even more intricate when you look at endorsements. In several states, the standard CDL endorsements cover broad capabilities, while others peel back a layer and require a specialized endorsement for towing. A common example is a state’s “W” endorsement for towing operations, which signals that the driver has been tested on the knowledge required to secure loads, manage towing gear, and handle common emergencies related to towing. In New York, for instance, a driver with a Class A, B, C, or Non-CDL Class C license can obtain a towing endorsement by passing a written test alone. This arrangement allows the operation of certain tow trucks that meet defined criteria, particularly for non-commercial towing scenarios. Yet if the work crosses into interstate commerce or pushes the weight thresholds beyond those carved out for endorsement-only operation, a full CDL becomes necessary. These rules underscore a broader truth: even when the CDL itself isn’t mandatory, the knowledge and capabilities to perform towing safely are still required. The endorsement acts as a formal recognition of that knowledge and a commitment to compliance with the associated procedures, from securing a vehicle properly to controlling a winch and stabilizing loads.

The “T” endorsement, referenced in some state regulations, adds another layer of complexity. Although originally associated with special towing considerations in certain jurisdictions, these endorsements can be essential for drivers who regularly move vehicles in commercial settings or whose fleets operate under particular weight or route restrictions. The exact scope of a “T” endorsement varies by state, and in some places, it is part of a broader framework that includes supplemental tests or endorsements tied to specific vehicle configurations. For operators, this means that a straightforward call about CDL status is rarely enough. You must look at how your tow truck is built, what it’s designed to tow, where you’ll be operating, and which endorsements your state expects you to carry.

To navigate this landscape, consider the practical steps that a prospective tow truck driver should take. Start with the GCWR of the tow truck and the vehicle you intend to tow. If that figure sits above 26,001 pounds, you can reasonably expect a CDL to be required, particularly if you anticipate interstate work. If you stay below that threshold in a single-state operation, there may be room for a non-CDL license with the appropriate endorsements. The next step is to verify state-specific rules. Some states align their weight thresholds with FMCSA, while others add local requirements tied to the commercial nature of towing services or to the specific classes of towed vehicles. In many cases, the DMV will require you to carry a “W” endorsement, while others may require the broader CDL class or a “T” endorsement for certain activities. Regardless of the path, the DMV’s official guidance and the FMCSA’s federal framework together determine what you must hold to legally operate a tow truck in your area. The precaution here is simple: rules can change, and they differ from one state to the next. If you’re moving between jurisdictions, your licensing needs can shift as you cross state lines.

For operators who are evaluating licensing options as part of starting or expanding a towing business, it helps to think about the licensing decision in two layers. First, does the operation ever involve moving vehicles with a GCWR over 26,001 pounds or engaging in interstate commerce? If yes, a CDL is the practical baseline, and likely a non-negotiable investment in time and testing. Second, even when a CDL isn’t strictly required, the endorsements and knowledge base matter. They influence risk management, insurance considerations, and the ability to perform the job safely and legally. In this sense, the licensing decision isn’t merely a credentialing hurdle. It is a foundation for professional practice, training, and the credibility that comes with operating on public roads. The responsibility extends beyond whether you personally hold a CDL; it includes your understanding of load securing, proper winching technique, and the ability to respond to roadside emergencies. The practical takeaway is that licensing decision points exist regardless of where you operate. You’ll likely need to spend time with your state DMV, read the state’s detailed guidance, and perhaps seek a career counselor within the regulatory framework to map out the exact path for your specific tow truck and intended routes.

If you’re curious about how the financial and equipment calculus mirrors the licensing decision, consider the broad impact on your business planning. The license you choose affects insurance costs, fleet maintenance planning, and the ability to hire or recruit drivers who can legally operate the equipment you rely on. A heavier tow truck or a more ambitious set of towing operations may justify the investment in a CDL as a standard requirement from the outset, rather than facing a late transition and the potential compliance challenges that come with expanding into heavier loads. The licensing path you settle on should align with your long-term goals for fleet growth, service areas, and the regulatory environments in which you will operate. In this sense, licensing becomes part of a strategic plan rather than a one-off hurdle.

For a practical look at the vehicle side of the decision, you can explore how much is a tow truck. This resource can give you a sense of the baseline costs and the breakpoints where licensing decisions become more than academic. how much is a tow truck. While price alone isn’t a licensing criterion, understanding the mix of equipment, weight ratings, and maintenance requirements helps you prepare for the licensing and endorsements that will accompany those choices. The licensing decision is intertwined with the equipment you select, the services you offer, and the markets you intend to serve.

Ultimately, the best path to clarity is to check with the state’s DMV and review the FMCSA guidance. The federal standard sets the floor, but state variations determine the ceiling of flexibility in your daily operations. Keep a current copy of both the FMCSA requirements and your state DMV rules handy, because the line between CDL-required and non-CDL operations can shift with changes in vehicle weight, tow configurations, and regulatory emphasis. By staying proactive—mapping GCWR to actual load scenarios, confirming endorsements, and understanding interstate versus intrastate implications—you’ll be better prepared to plan for licensing, training, and the ongoing compliance that accompanies towing work. The chain from weight rating to licensing to on-road practice is tight, but with careful planning, drivers and operators can navigate it with confidence and maintain safety for themselves and everyone sharing the road.

External reference: For the official federal framework on Commercial Driver License requirements and how they apply to tow-truck operations, see FMCSA CDL requirements.

Weight Limits, Licenses, and Tow Trucks: A Practical Guide to CDL Requirements and Road-Ready Towing

The question of whether a commercial driver’s license (CDL) is needed to operate a tow truck sits at the intersection of weight, regulation, and practical service needs. For most tow operators in the United States, the answer hinges on the combined heft of the tow vehicle and whatever it is hauling. The federal standard set by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) is clear: if the gross combined weight rating (GCWR) of the towing unit and its load exceeds 26,001 pounds, a CDL is required. This rule acts as a compass for fleets and solo operators alike, guiding decisions about licensing, training, and the legal scope of daily work. But the real world of towing is rarely a single line on a chart. It is a tangle of different weights, equipment configurations, state rules, and operating environments. To navigate it well, a tow operator must understand how weight classes are defined, how they interact with the vehicle and trailer, and how state regulations might tilt the balance toward one class of license or another. The core concept is GCWR, but the reasoning behind it involves a broader frame: GVWR, curb weight, payload, the type of towing operation, and the safety margins that keep drivers and the public out of danger. In practical terms, the GCWR is the maximum allowable combined weight of the tow truck and the trailer it pulls, including any cargo, fuel, passengers, and the towed vehicle itself. If you picture a tow truck with a GVWR around 25,000 pounds and you hook a 10,000-pound car to it, the GCWR climbs to 35,000 pounds. That jump alone crosses the 26,001-pound threshold and triggers CDL requirements. This arithmetic is not a mere academic exercise; it determines which licenses you hold, what endorsements you need, and whether you must pursue additional training before you step into a municipal yard, a wreck site, or a highway shoulder to begin a recovery operation.

The regulatory landscape is also nuanced by exceptions and special use cases. Even when the GCWR sits below the threshold, there are scenarios that can require CDL credentials. Transportation of hazardous materials in quantities that trigger CDL rules, or operating a vehicle designed to transport more than 15 passengers (including the driver), are standard exceptions. In most routine tow operations—where the loads are non-hazardous and the passenger count remains under 16—the GCWR is the major determinant. This emphasis on GCWR helps prevent a mismatch between the vehicle’s physical capability and the operator’s training and regulatory approval. For anyone tampering with the math, the FMCSA’s official guidance is the most reliable anchor. The FMCSA site consolidates the regulatory framework and points to the exact language in the code that governs licensing, endorsements, and vehicle classifications. While the federal baseline is essential, the complexity of state rules means that a driver must also consult state authorities for licensing particulars, which can vary by jurisdiction and by the nature of the towing operation.

State variation adds another layer of consideration for tow operators who work across borders or who run small fleets that serve a single metropolitan area with adjacent counties. California’s regulatory approach emphasizes a combination of GVWR, GCWR, and the specifics of the towing activity. The California Public Utilities Commission and the Department of Motor Vehicles lay out criteria that typically push toward Class B or Class C CDLs, depending on the weight category of the towing unit and the typical composition of the load. In practice, many towed operations in California fall under Class B for heavier trucks or Class C for lighter configurations that still require careful licensing. The key takeaway is that state rules can require more stringent licensing than the federal minimum, especially for commercial towing services that operate in urban environments with tighter curbs and higher incident volumes.

Texas presents a different regulatory posture. The Texas Department of Public Safety aligns CDL requirements with GCWR thresholds, and the licensing duties extend to the standard slate of endorsements and testing, including the medical and vision checks that accompany CDL issuance. For many operations in Texas, a Class A, B, or C CDL may be necessary, determined by the combination of the tow truck and its trailer and by the nature of the load. In states with large, diverse tow markets, the practical effect is that operators cannot assume a universal license will suffice; they must assess the full weight profile, the type of towed load, and the intended routes. Florida follows a similar pattern, with its own set of thresholds and endorsements. The Florida Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles (FLHSMV) framework typically requires a Class B CDL for heavier tow units and a Class C for lighter configurations, subject to additional state-specific rules about age, training, and testing.

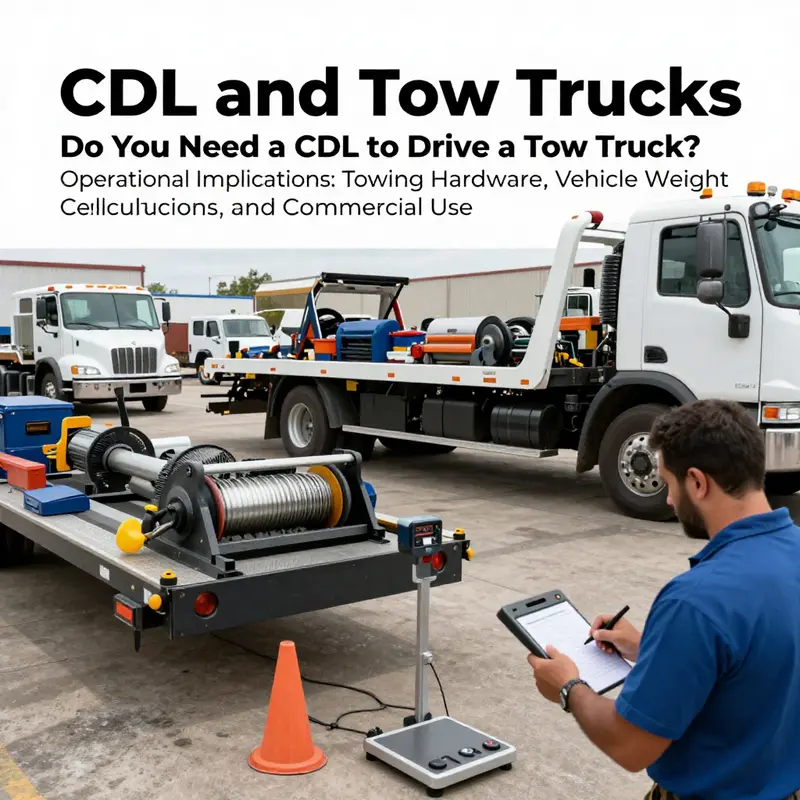

The weight question, however, does not exist in a vacuum. The hardware used to perform towing tasks matters as well. Tow trucks are not monolithic; they range from wheel-lift units that slide under a vehicle and lift one end off the ground, to hydraulic booms that can pull and lift in more complex recovery situations. There are saddle or cradle-style units designed to cradle a vehicle’s frame for stability, flatbed or rollback units that load the entire vehicle onto a platform, and integrated systems that combine several capabilities into one chassis. Each design has advantages and trade-offs in terms of speed, safety, and the kind of licensing and endorsements that operators may need. A wheel-lift, for instance, is compact and quick in urban spaces, which suits short-distance towing and vehicles with front-wheel drive; yet it may pose risks of undercarriage damage on certain vehicle types. A boom/winch setup offers broad versatility for accident scenes where the vehicle cannot be driven, but because it can involve more complex operations and may engage more powerful hydraulic systems, it can influence the required training and compliance measures. Flatbeds protect vehicles from road debris and weather during transport and are often the preferred choice for dealership moves or delicate recoveries, but they demand more attention to loading procedures and longer cycle times. Integrated units blend capabilities to meet the widest range of situations, enabling a single driver to deploy wheel-lift, boom, and flatbed functions as the scene demands. In all cases, the licensing framework—CDL, endorsements, and operator training—must align with the operational profile of the hardware and the weights involved.

Within this landscape, the specific endorsements and classifications become more than bureaucratic labels. The industry has long recognized a T endorsement for towing operations as a specialized skill set, reflecting the additional knowledge required to safely manage vehicle recovery, load securement, and navigating traffic with a towed or partially restrained vehicle. The T endorsement, alongside standard CDL categories, serves as a signal that a driver has training relevant to the unique hazards of towing work, including the proper use of tie-downs, wheel nets, stabilizers, and other securing mechanisms that prevent shifting loads on the road. Driving a tow truck is not merely about getting from point A to point B; it is about controlling a heavy, sometimes unstable combination of vehicle and cargo, with balance, braking, and steering demands that demand professional-level competence.

A critical element that ties license requirements to daily practice is weight calculation. GVWR refers to the maximum weight the tow vehicle can safely handle when fully fueled, loaded, and equipped with standard features. Curb weight is the vehicle’s own weight ready to drive, without passengers or cargo. Payload is the difference between GVWR and curb weight and marks the maximum load the vehicle can carry in addition to its own mass. GCWR is the sum of the tow vehicle’s weight and the trailer’s maximum permissible weight. When the two-vehicle combination’s GCWR crosses the federally established 26,001-pound threshold, a CDL becomes the regulatory pathway, with additional considerations for transporting hazardous materials or large groups of passengers that can push toward higher endorsement requirements. The formulas that govern these calculations are straightforward, but their practical implications are complex. The towing operator must not only know the numbers but also how to apply them in real-world loading scenarios. A payload that appears modest on paper can become critical if distribution skews toward a single axle, raising handling concerns and braking demands. The GCWR must be treated as a ceiling that cannot be exceeded, even if the sum of the individual weights stays within separate limits. For this reason, most fleets insist on a cautious approach: if there is any doubt about the GCWR or the load distribution, operators are instructed to err on the side of a higher class license or a lighter load until a precise calculation confirms safety and compliance.

These weight calculations are complemented by a practical emphasis on safety and compliance. Never exceeding GVWR or GCWR is not simply a legal strictness; it is a posture that protects drivers, other road users, and the integrity of the vehicle. Even when calculations suggest a permissible load, effective load distribution matters. Uneven weight across axles can affect braking performance, steering response, and tire wear. Before setting out, drivers should consult the owner’s manual for exact GVWR, GCWR, curb weight, and towing capacity; in many cases, actual loading differs from theoretical calculations due to fuel levels, passengers, or specialized equipment carried on board. When in doubt, a weigh station can provide an accurate assessment of a loaded combination and help confirm that the operation sits within safe and legal limits. The aim is not merely to satisfy a regulatory checkbox but to ensure predictable handling, shorter stopping distances, and a margin of safety during turns, lane changes, and emergency maneuvers.

The practical path for a tow operator, then, blends licensing with operations. For commercial towing services, the federal GCWR threshold defines the license tier, while state rules may impose stricter classifications and additional endorsements. When a driver is contemplating cross-state work, the prudent course is to verify the specific licensing requirements for every state in which the driver will operate. The licensing decision is inseparable from the service model: does the business intend to transport beyond a local area, or maintain operations strictly within municipal or county borders? Will the operation involve hazardous materials, long-haul routes, or passenger transport beyond the driver’s vehicle? Each of these factors could shift the license category, the endorsements required, and the training standards enforced by regulators.

Beyond licensing, the economics of tow work often comes into play. The cost and availability of licenses, the time required to complete training, and the ongoing compliance obligations can influence whether a single operator shifts toward a heavier, more capable tow unit or adopts a lighter configuration that fits a narrower service window. The financial implications extend to insurance, maintenance, and the risk exposure that accompanies operating heavy equipment on crowded streets. For anyone evaluating the overall investment, the question of licensing is not separate from the cost of equipment and the expected workload. A thorough assessment considers not only the purchase price of a tow truck and the cost of securing appropriate licenses but also the long-term expenses of keeping the vehicle compliant, the endorsements current, and the operator trained to handle a spectrum of recoveries—from routine roadside assists to complex multi-vehicle incidents.

To connect the technical thread to everyday decisions, consider how a driver or small fleet might approach this landscape. If the job primarily involves short, urban recoveries with lighter loads, one might anticipate a Class B or Class C scenario, depending on local weight caps and the specific vehicle configuration. If the work requires moving heavier trailers, multiple vehicles, or occasional cross-state deployments, the calculus shifts toward Class A, with the corresponding endorsements and training tied to longer, more complex routes. Regardless of the chosen path, a deliberate, standards-aligned approach to licensing ensures legality, safety, and the capacity to meet customer expectations in high-pressure situations. For readers weighing the practical cost and career implications of owning and operating a tow truck, it helps to understand the broader picture, including the ownership costs and licensing requirements that accompany the tool—the vehicle—before the road is ever met with a tow request. For a practical peek into the financial side of owning a tow truck, see How Much Is a Tow Truck?

As readers move from the public-facing question of CDL necessity to the inner mechanics of how these licenses pair with vehicle weight and recovery methods, a key truth emerges. Tow trucks are crucial, high-precision machines that demand disciplined training, careful weight management, and an up-to-date grasp of regulatory requirements. The road rarely stays still, and neither do the rules that govern it. The best operators treat licensing and weight calculations not as separate hurdles but as a single, integrated system that informs every decision—from which truck to buy to which load to accept, to how to document every step in a way that stands up to audits and roadside inspections. In that sense, the CDL is not merely a credential but a reliability framework: it signals to clients, insurers, and regulators that the operator is prepared to handle the realities of modern towing with competence, safety, and accountability.

External resource for official guidance: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/regulations/vehicle-requirements/commercial-driver-licenses

null

null

Final thoughts

The answer to do you need a cdl to drive a tow truck is not a single yes or no. It depends on the combined weight, the specific vehicle and equipment, the intended use, and the state in which you operate. By understanding the federal GCWR thresholds, recognizing state variations and endorsements, and applying careful weight calculations to your towing setup, you can determine whether a CDL, and potentially a T endorsement, is necessary for your operation. The practical takeaway for Everyday Drivers, residents, truck owners, repair shops, dealerships, and property managers is to start with your tow truck’s GCWR and your most common towed load, verify state requirements where you operate, and plan for any endorsements or licensing changes before you tow commercially. This disciplined approach enhances safety, reduces exposure to penalties, and keeps your towing activities aligned with both federal intention and local practice.